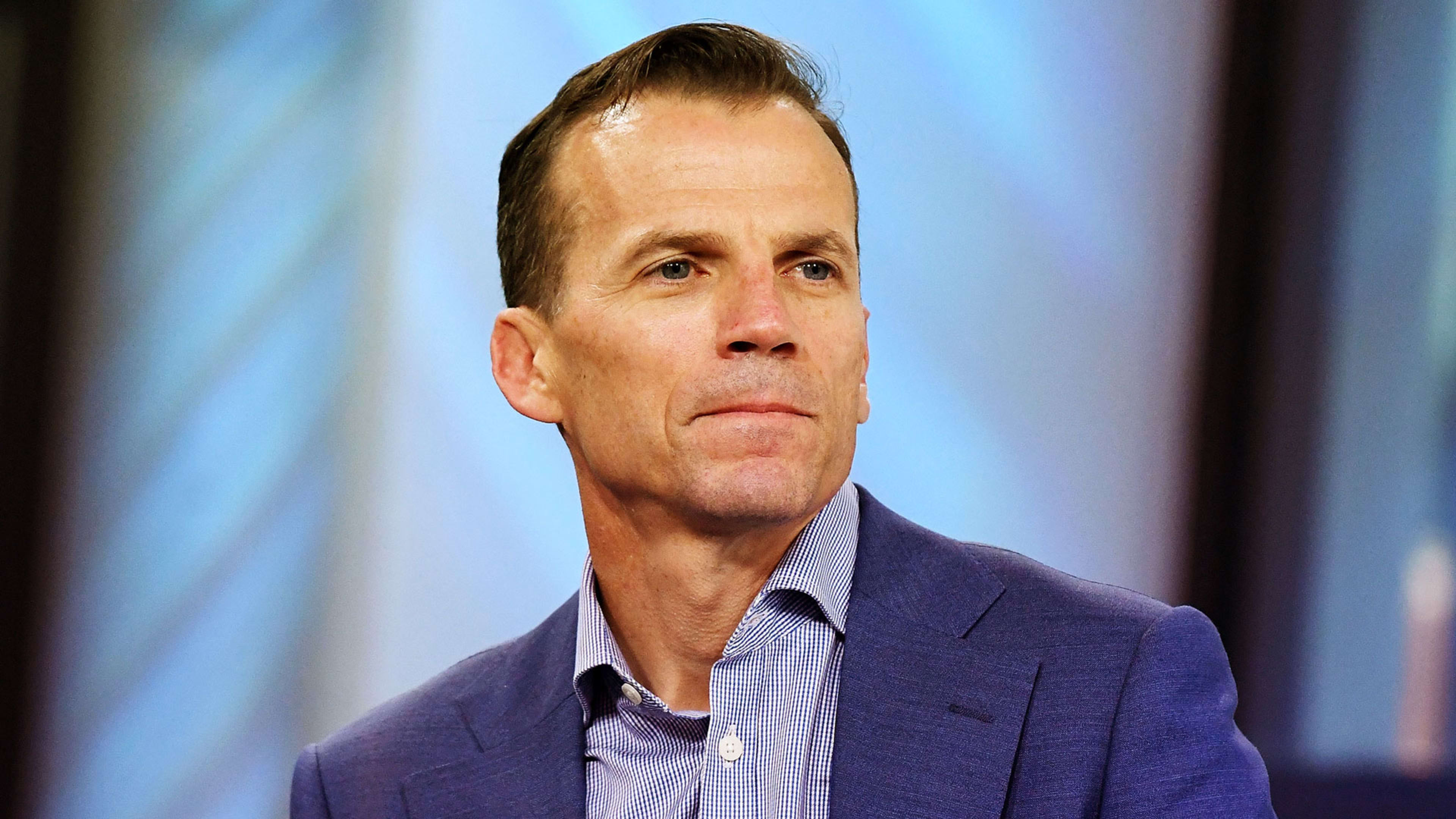

During his 15-year tenure in the U.S. Navy, former SEAL Chris Fussell found that the higher his rank, the more sidelined he felt. “As you move up a traditional, sort of bureaucratic structure, there’s a certain point at which you realize, well, I’m not really on the implementation or execution side—I’m not on the battlefield. I’m an operations person who’s overseeing multiple units that are out on the ground doing the job,” Fussell recently told Fast Company.

This type of movement away from the action is pretty common in civilian workplaces, too. With each promotion, you tend to get further removed from the day-to-day goings-on of your organization. As Fussell writes in his new book, One Mission: How Leaders Build a Team of Teams, “bureaucratic advancement means fewer peers, more span of control, generally an increasing information-pump function, and increased distance from the actual implementation of whatever it is the organization does.”

If Fussell was supposed to be an “information pump,” though, he felt like a jammed one—he realized that he’d become more of a bottleneck to his team than much else. But then he realized it wasn’t completely his fault.

Moving Faster Amid Information Overload

It was an organizational problem. “The reality, as the battlefield taught us,” Fussell writes, “is that a 20th-century organizational system is simply insufficient for the speed of the information age.”

This was a lesson the military learned firsthand after the start of the so-called “War on Terror” in 2001. Early on, Fussell says, senior leadership began grappling with how to make the armed forced more agile and adaptable when faced with a decentralized adversary and a glut of data. Too much information was being disseminated too slowly, which meant changes in strategy trickled down too slowly, too. Eventually, Fussell recalls, his team was was holding all-hands videoconference meetings on a daily basis, trying to keep up to speed.

Now a partner at the McChrystal Group, founded by Stanley McChrystal (Fussell’s lieutenant general when he entered the Joint Task Force) [he was also McChrystal’s aide de camp in 2007 and 2008], Fussell now helms the organization’s Leadership Institute, where he finds companies facing similar problems as he did with the SEALs. One “core question” he says many still struggle with is, “How often are you really realigning yourselves on strategy? And does it need to be faster, based on how quickly your market actually changes? The answer is usually yes.”

But adapting faster in a data-saturated environment is hard. It often means regular strategic discussions, more transparency, and changing how information gets funneled through an organization—to prevent clogged information pumps and shield leadership from gobs of useless data. With these complicated challenges in mind, and drawing on his Navy experience, Fussell wrote One Mission to be as “as close to a practical guide to this sort of change process as possible.”

Helping Big Companies Stay Nimble

Fussell’s book includes case studies on various companies the McChrystal Group has worked with, from financial software firm Intuit to apparel giant Under Armour.

For Intuit, which owns tax-prep software TurboTax and personal finance app Mint, Fussell says the challenge was to consolidate the company’s various business units over the course of 2014 so it could unify as “one Intuit.” The company was worried about upstarts that were quicker on their feet. “For Intuit and these ‘legacies’—once insurgents in their own right—it was now a question of, ‘How do you take a company at scale and recreate the adaptability and intimacy of a startup?'” Fussell writes in his case study.

In the case of Under Armour, which Fussell and his team consulted with for a year starting in September 2014, the McChrystal Group helped streamline communications around the company’s supply chain. While the company’s supply-chain division may have felt like “the materials are on the boat,” Fussell explained, by way of example, “R&D realized that they want to make a change, and marketing finds out that the color scheme should be completely different, so the boat has to turn around.”

But once those parties started communicating more frequently, Fussell says, “they could see problems coming six months down the road and solve for them before it was too late.” In other words, the whole organization needs to pump information, not just a few key influencers.

Fussell says he usually works with companies that fall broadly into one of two categories. The first includes big enterprises like the military that have been around for years and want to “reverse engineer” themselves to recapture a startup-like energy. You could count General Motors in this camp; under CEO Mary Barra, the automaker has been trying to shake up its culture in order to lure top tech talent from the startup world. And then there are small organizations at “the tipping point,” says Fussell, who are often asking, “How do we maintain this culture as we scale up?” This has been a key priority for Facebook over recent years.

For companies small and large, old and new, the through-line as Fussell sees it is transparency—either introducing it into existing corporate structures or preserving it when a scrappy startup grows up.

It’s The Same Goal Everywhere: Win

Fussell says people often mistakenly think of the military as fundamentally different from other organizations, because the stakes are much higher when it’s a matter of life or death.

But in his experience, “That’s not really what most people wake up thinking about. The idea of losing is a huge negative, but not getting shot at or loss of life—that’s just a reality of the battlefield,” Fussell says. “Not to say that it isn’t important—it’s just not top of mind every single day with most of the thinkers inside the service.”

Instead, he says he’s seen more similarities between civilian and military organizations than differences, particularly when it comes to the challenges their leaders face. “What they’re thinking is, ‘I don’t want to lose,'” he says of senior military officers. “And that mind-set is very similar to industry, which is, ‘Hey, we’ve got a good organization here, and we want to win. We want to come out on top.'”

As Fussell points out, winning demands agility and adaptability, regardless of industry. It’s less about individuals’ own abilities than whether those individuals can come together and communicate with each other—and get better and faster at it all the time.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.