Before he begins to tell me about living through Hitler’s rise to power as a young boy in Warsaw, Pinchas Gutter, now in his mid-eighties, seems to pause and collect himself. His hands grip the armrests of his chair.

“Before the war, in the Yiddish newspapers, they always used to show Hitler like a caricature, like a quasi-comic figure,” Gutter tells me. “And then in the Warsaw ghetto, once we started suffering at his hands, the majority of people I heard–and it wasn’t my opinion because I don’t think as a child I formed an opinion–was that he was a madman. That Hitler was not a person. They either called him the Devil or a madman; nobody even called him a beast, because beasts did not behave the way that he did.”

I had asked Gutter to tell me how old he was when Hitler came to power. He didn’t tell me that, exactly, though he has the precise answer on file somewhere: The version of Gutter I was speaking to was a hologram, compiled from footage collected over a period of five days and over 25 hours filming the answers to over 2,000 questions.

The hologram–1 of 13 developed for the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation’s New Dimensions in Testimony initiative–is still in the pilot phase, and still learning. My conversation with Gutter, Stephen Smith, executive director of the Shoah Foundation, tells me, will be recorded and fed back into the natural language processing software developed by USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), that the hologram pulls from in order to answer any question someone might have about Gutter’s life before, during, and after the war.

Talking with the hologram Gutter is a surreal experience. The hologram can be set up anywhere; we’re in a bland conference room in the middle of midtown Manhattan, and Gutter, life-size and sitting against a black background, is projected onto a screen that hangs against one of the walls. He is very obviously not a real person, yet when I stop my slew of questions–“What was it like being separated from your family? Can you describe the day you were liberated?”–and turn to speak with Smith and Maio, I feel like asking Gutter to excuse me for being rude. Because while he’s far from lifelike, Smith and Maio have meticulously ensured that the answers surfaced by the algorithm mimic natural conversation as much as possible.

“The field has been concerned about what’s going to happen to Holocaust education when survivors are no longer present,” Maio says. It’s estimated that in a decade’s time, every person who, like Gutter, lived through the atrocities of the Holocaust will have passed away. And to Smith and Maio, the loss of in-person testimonies will be profound. “We find that when a survivor speaks to a classroom or in the public domain, that impact that the meet-and-greet, the questions and answers, has on people and how we understand that history is significant,” Maio says. “We don’t want to lose it.”

The interactive hologram, Smith says, doesn’t replace the testimony of a live person. It can’t. But amid all the talk about future-proofing the wealth of history and emotion contained in the personal testimonies of Holocaust survivors, Smith and the Shoah Foundation are attempting to preserve it for as long as possible. By collecting more data than they needed, in the highest resolution possible, and keeping that data neutral and raw, the Shoah Foundation is accounting for the fact that no one really knows what future technology will look like or enable. In the augmented-reality field, it’s an unusual approach. “Generally speaking, in the industry around interactive media, everybody is building content for specific platforms and engines,” Smith says. The Shoah Foundation’s comprehensive approach to data collection, he hopes, will allow this new wave of dimensional testimonies to adapt to future platforms that have yet to be invented.

But for Gutter, agreeing to pilot this new format of testimony necessitated a difficult journey back into the past. Just 14 years old when the war ended, Gutter eventually made his way to Canada, where he worked odd jobs and never spoke about what he went through during the Holocaust: being uprooted from Warsaw at the age of 11 and being taken to Majdanek, where his twin sister and parents were killed upon arrival; surviving a death march from another camp in Germany to Thereseinstadt in Czechoslovakia, which was liberated by the Russian army on May 8, 1945. But a professor at the University of Toronto knew of Gutter, and convinced him in 1992 to record his testimony for the archive she was compiling. Later, he met Smith, who recorded Gutter’s testimony for the Shoah Foundation, and who convinced Gutter to return to Poland with his family in 2002 to share with them his personal history that he’d so long kept quiet.

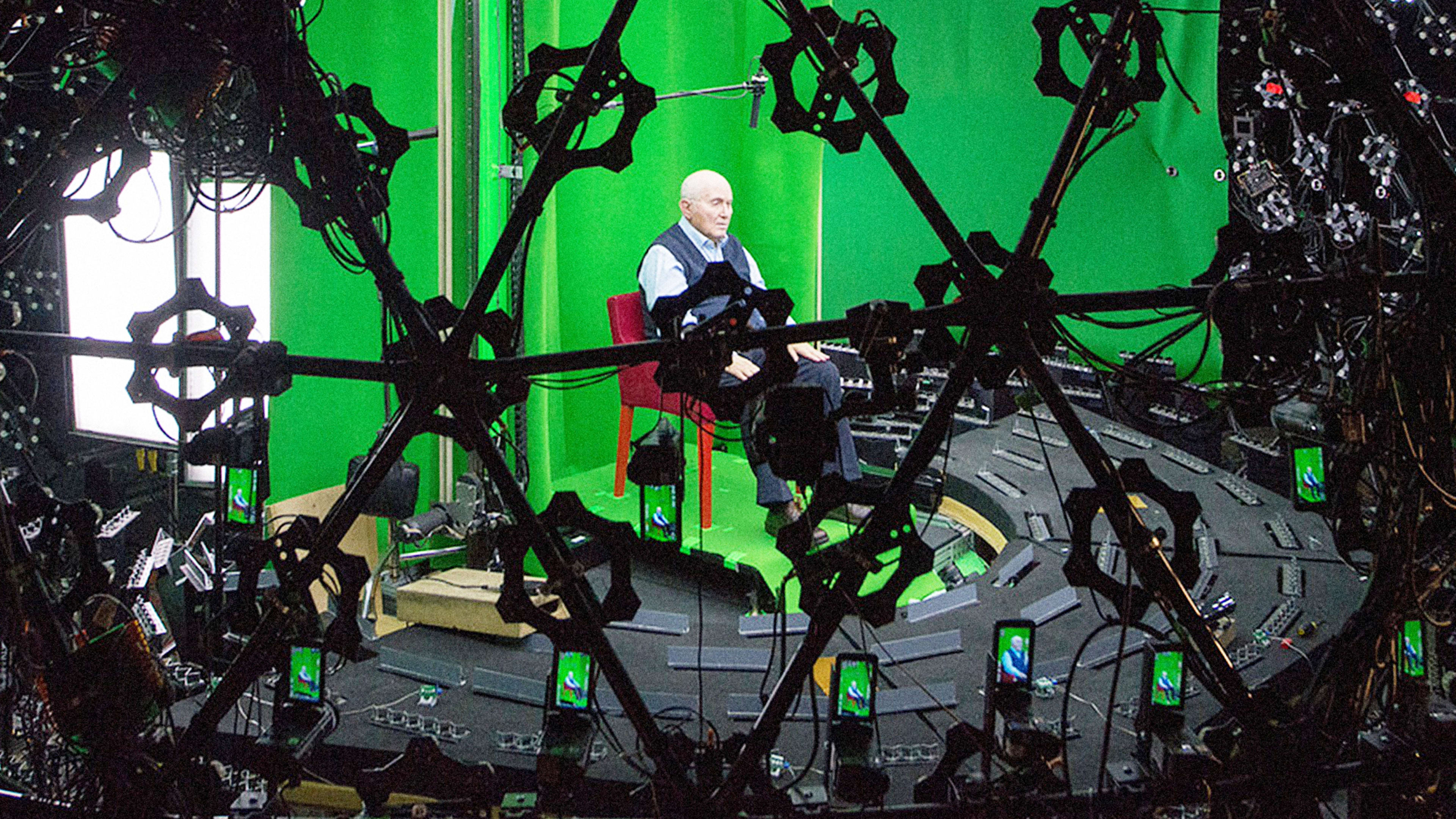

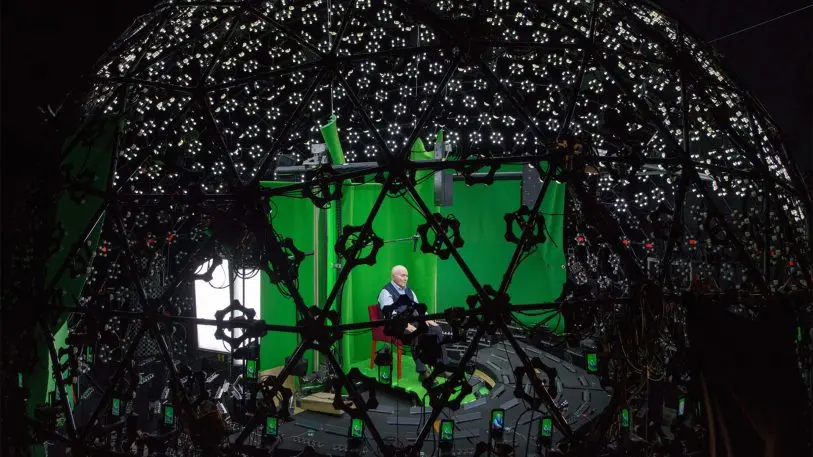

Yet translating the personal experience of the Holocaust to digital form was a taxing process. In a circular studio, around 50 feet high, Gutter sat in a chair in the middle of 52 cameras, arranged in concentric circles and all aimed at him, along with the 6,000 LED lights that illuminated the space. Though Gutter began the filming process in 2014, Smith, Maio, and the team at ICT have been working on developing the technology and the format since 2009. (Maio’s company, StoryFile, uses a less robust version of the technology to allow individuals to record recollections from their loved ones in a similar way.) Bound up in that process, Smith says, was finding survivors willing to share their story in this way. “It was tough, it was difficult, it was taxing,” Gutter says.

While many of the questions Gutter responded to came from the Shoah Foundation organizers, he also fielded questions from children, and people who have experienced the interactive as its been piloted over the past year in various institutions, like the Houston Holocaust Museum. Over time, Maio says, the algorithms embedded in the hologram will learn to respond to vocal cues signifying age, and will adjust its answers to the inquisitor’s demographic, and learn to respond to different versions of the same questions. “Every person has their own way of asking: ‘Do you believe in God?'” Maio says.

The first formal installation of the hologram will open at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie in October. Until then, the holographic Gutter will be learning and iterating through its various pilot appearances. The technological improvements, though, will only serve to better transmit the real Gutter’s message, which is to make real and permanent his firsthand knowledge of what happened in the Holocaust, and what can happen in any country, so future generations will not perpetuate the monstrosities.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.