Consumers and accessories makers have been somewhat slow to adopt the platform known as HomeKit since its debut three years ago. There are several reasons for that, and one of them is that HomeKit just isn’t a very sexy product. It’s no Apple Music. It’s hard to visualize. When you think of “HomeKit” what do you see? How do you think about a tech framework that ties together a bunch of rather bland home accessories?

But the new HomePod smart speaker, which Apple announced on Monday, could finally light a fire under the platform.

The $349 device, equipped with Siri, won’t become available until late this year, but Apple has already confirmed that HomePod will provide a much-needed natural language interface for HomeKit. HomeKit users will be able to speak commands to devices all over their home as if they were talking to another person in the room. HomePod owners won’t have to dig out their iPhone to order to get HomeKit to “open the drapes.”

The full details of HomePod’s functionality in the HomeKit home have not yet been disclosed by Apple, but the broad strokes are what you might expect. Apple told me users will be able to use HomePod to do anything they can currently do using HomeKit’s central control app in iOS, Home. Instead of tapping buttons to control their house, users will simply speak. And like Apple TV and iPad, HomeHub will be able to run automations and enable users to control home functions while they’re away from home.

But if Apple’s announcement is any guide, HomePod will be marketed as more of a smart music streaming device–a great-sounding delivery point for Apple Music–and not so much as a connected home device. That might be a wonderful way to get HomeKit in the door, so to speak. People might adopt the device for music and, like many Amazon Echo users did, later discover the hands-free joys of using it to control appliances and other devices around the house.

Singing From The Same Songsheet

The goal of HomeKit is to create an easy, “it just works” connected home experience for mainstream consumers, while providing accessory-makers with automation, security, and voice control functions they may not otherwise be able to build themselves. At WWDC, Apple announced that HomeKit can now turn on AirPlay-enabled speakers in the home, can control faucets and sprinklers, and can trigger accessories, like lights, to come on only for a pre-defined period.

But getting a bunch of accessory devices from different categories to work in concert, together, is a hard technical challenge. In order for a Schlage door lock to trigger a Philips light the two things must use the same basic language. Fortunately, Apple has the resources (and the patience) to do it.

To architect the guts of HomeKit, Apple had to create a platform that could make sense of a wide variety of devices, all of which do very different things in very different ways. But HomeKit insists on treating all accessories in a given category equally: It makes no distinction between one ceiling fan and another, one thermostat and another. HomeKit tells a Philips light to dim by 30% in the same way it tells a Nanoleaf light to do so. Communicating with each device in a unique way would lead to huge complexity that would only get worse as more devices joined the ecosystem.

An accessory developer, in order to get a product HomeKit-certified, has to make sure its device can respond correctly to the full set of commands a user can send to it from the Home app. A thermostat-maker might comply with the spec by creating a set of 30 functions a consumer is most likely to use, like “turn up heat by five degrees,” “shut off fan,” and so on. By contrast, to integrate accessories with Amazon’s Alexa, an accessory-maker typically uses an API (application programming interface) to link its own software to Alexa via Amazon’s cloud. To work with Google Home, a device maker must build a smart home app for Google Assistant.

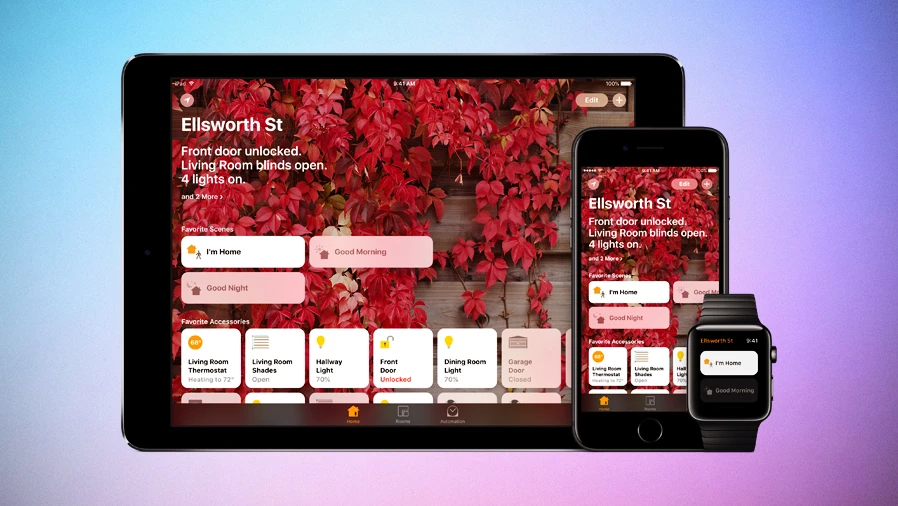

With HomeKit-connected accessories in a home all responding to a standardized, and abbreviated, set of function requests, a central point of control for all the devices becomes possible. The Home app, which Apple released with iOS 10 in 2016, is an important differentiator in HomeKit. The Home app’s main job is to let users control single accessories or groups of accessories (“scenes”) and to order devices to do things automatically when certain conditions are met.

A “Goodnight” scene might turn the lights off, lower the shades, and turn down the heat. An automation might turn on a fan when a sensor detects that air quality has fallen below a certain threshold. Another automation might switch on the hot tub at a prescribed time, or when the homeowner crosses a geofence coming into the home.

The Amazon Alexa app allows Echo owners to do some simple grouping of devices (like linking a group of living room lights to turn on together). But to do larger groupings with more detailed commands, or time-based device triggers, an Alexa-friendly home hub like the Logitech Harmony is needed. Google’s Home app offers basic device controls, but it can only group devices by the rooms with which they were associated on setup. And there are no automations.

Setting Up The Gear

Perhaps the coolest thing about HomeKit is that it takes away much of the headache of setting up or adding new accessories. To add a new device to HomeKit, the user aims their iPhone camera at a code printed on the back of the accessory, or on the setup instructions included with the device. At that point, two things happen: HomeKit automatically connects the accessory to the Wi-Fi network the user’s Phone or iPad already connects to, and to the HomeKit framework in iOS. So there’s no fumbling with Wi-Fi passwords. It just happens.

Compare that out-of-the-box simplicity to that of other connected-home device makers. To set up new accessories for control with Amazon Echo or Google Home, users download the accessory-maker’s app, then go to the device settings to connect the accessory to the same Wifi network the Echo or Home lives on. Alexa users click on a button within the accessory app to enable it for voice control. Google’s Home app asks the user to choose the brand of the new device from a list, then asks the user to log into their account at the accessory maker’s site.

With HomeKit, taking a picture of a device’s code during set-up ensures that the new device and the iOS device are within close range of each other. This is important for security reasons. In other systems, Apple says, a new device begins broadcasting a wireless signal to announce itself as soon as it’s turned on, which could be exploited by a hacker lurking outside the home.

Beefing Up Security

Talking to Apple people, you quickly notice that they are almost obsessive about making HomeKit airtight against hacks.

That all data flow is end-to-end encrypted isn’t surprising, but HomeKit is unique among connected home platforms in that it totally shuns the cloud. HomeKit operates purely on a device level, communicating directly via Bluetooth and Wi-fi between iPhones, iPads, Apple TV, and third party accessories in the home. Apple believes data constantly moving back and forth from various first- or third-party clouds could create attack vectors that hackers could exploit.

HomeKit is also designed to avoid capturing personal data, Apple says. All accessory usage data is locked down on the iOS device, available only to the user (with a passcode) and not accessible by Apple. This claim fits with Apple’s business model: selling hardware does not rely on the collection of user data, a fact the company likes to emphasize. (Also recall Apple’s high-profile face-off with the FBI over smartphone data encryption last year.) Google’s business, meanwhile, depends on the collection of user data to target ads, and Amazon’s business depends on the collection of user data to market products online.

Control Freak vs. Facilitator

Apple’s tightly-controlled approach to the connected home stands in sharp contrast to the approach used by Google and Amazon, whose platforms connect and manage third-party accessories in a much less involved way.

Amazon has given accessory-makers lots of freedom in defining how their Alexa skill is called up. Two different connected light bulb makers, for example, might use very different trigger words to call up their functions via Alexa. Amazon would simply make sure that Alexa understood both. Accessories makers like that freedom and ease of integration.

That’s why so many accessories makers have hurried to develop a skill for Alexa. Amazon says there are “hundreds” of them. Google Home has been available for only about six months and already Google has “more than 70” accessory maker partners. The downside is that this approach can make for a decentralized and inconsistent user experience.

Perhaps because it’s harder to integrate with HomeKit, accessory-makers have only gradually bought into Apple’s vision for the connected home. Roughly 60 accessory-makers have certified (or told Apple they intend to certify) around 130 HomeKit-enabled products. And, perhaps partly because of the limited choice among HomeKit-certified accessories, consumers haven’t exactly rushed to embrace HomeKit as their de facto connected-home technology.

But, in the wider view, the connected home concept has a feeling of inevitability about it. Digitization is seeping in everywhere, and it will come home. More consumers will become more aware of the cool factor of automatically switching on air purifiers or coffee makers, or remote controlling the home from the road or the office via the app.

And many consumers are just now getting turned on to the idea of speaking to appliances as if they were people, just like they do in sci-fi (“Open the pod bay doors, Hal.” OK, bad example but you get my drift). Apple already had a very strong home-control platform, and even though it was a little late to the party, it now has the HomePod, which may come to be seen as the main vehicle for the personality of the connected home–Siri.

As Apple’s Phil Schiller said during the HomePod product announcement, a smart speaker must “rock the house.” More importantly, it must rock the home.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.