In a corner of the Swiss Alps, a snow machine pointed at a patch of ice is testing a new theory: Could manufactured snow help stop the retreat of a glacier?

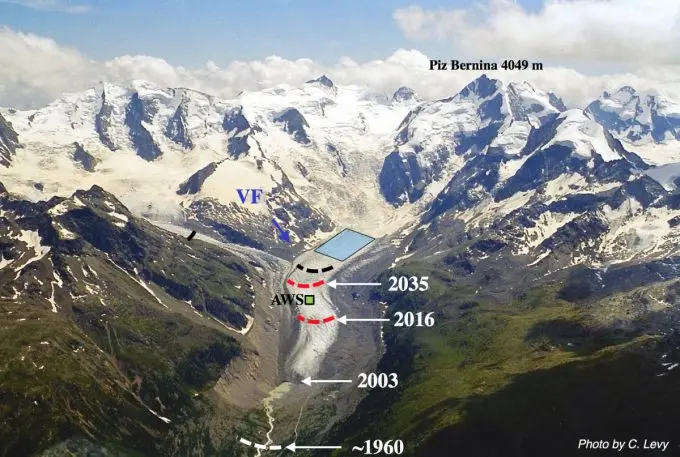

Since 1860, the Morteratsch glacier in Switzerland has shrunk back 2.5 kilometers, or more than half the length of Central Park. Each year it’s losing another 115 feet of ice. Other glaciers are also shrinking quickly–but because Morteratsch draws crowds, the local community decided to reach out to researchers to try to find a way to preserve it.

“This particular glacier is a very big tourist attraction,” says Johannes Oerlemans, a glaciologist from the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research Utrecht in the Netherlands who was one of the researchers the community approached for help. “It’s one of the few that is very easy to reach. We always say it’s the single glacier in the Alps that you can reach by wheelchair.” Now the glacier has retreated so much that it’s barely visible from the most accessible viewpoint at the end of a road.

“We think that’s impossible,” Oerlemans says. “It’s 100 times bigger. You cannot cover a glacier of that size with fleece. But then we looked at other options, and we thought that perhaps something can be done by trying to keep part of the melt zone white in summer.” A cover of snow would reflect away sunlight, and insulate the ice. “If you do this in an area that’s large enough, you may at least be able to slow down the retreat of the glacier.”

In models, Oerlemans and other researchers found that it should be possible to maintain a cover of snow on the glacier through the summer by making artificial snow from local meltwater. Using standard snow machines wouldn’t be practical–the project would require thousands of them–but the researchers think that a different kind of technology might work.

While the technology has yet to be designed, the basic idea is to attach a snow machine to an aerial tramway that is suspended between mountain peaks, so that it could move back and forth to cover a large surface with snow. “It’s not without problems, but I think in the long run it has a better chance that you can cover a large area,” he says.

The current study, with a single snow machine dumping snow on a 200-square-meter patch of ice, is the first step in determining if the plan might work. “We’re doing a pilot study on what we call a baby glacier–it’s a very small patch of ice made artificially for us, with just one snow machine, and we have a weather station. We try to get this through the coming summer. When this works, we’ll be more confident that it could also work on a larger scale.”

Even if it does work, it’s likely to be a somewhat temporary solution. (It would also likely be expensive; the pilot study alone has a cost of 60,000 euros, plus support from partners like a cable car company.) Using two decades of weather data from the glacier, the researchers found that it’s only cold enough to make snow 5% of the time in the summer. Right now, that would work–it would still be possible to produce snow faster than it melts away. But as summers get hotter, fake snow may no longer be an option. Summer temperatures in the Alps are already rising 2.5 times faster than the global mean.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.