Poverty is normally seen as a deep, complex, social problem. But to the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman it comes down to something simple: a lack of cash.

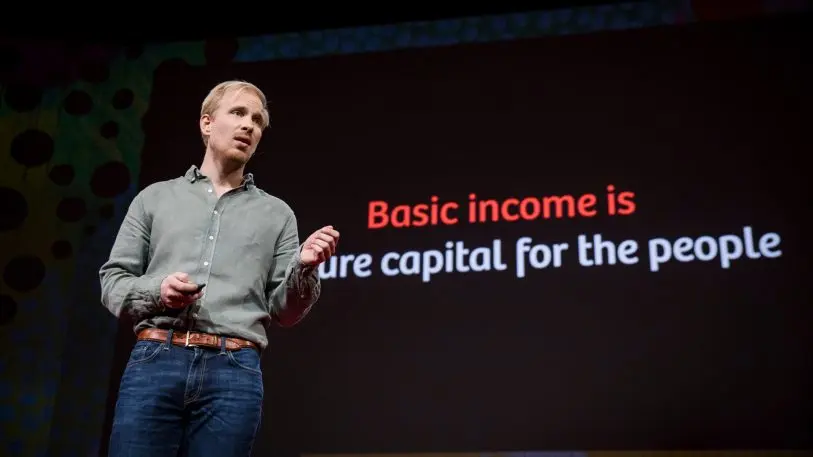

In a well-received talk at TED’s 2017 conference, Bregman argued that we can end poverty by giving people the cash they don’t earn–that is, by adopting a universal basic income. And, contrary to some basic income naysayers, he says the policy needn’t be particularly expensive. Raising every American above the poverty line would cost about $175 billion, he says–about a third of what we spend on national defense.

Bregman, author of the book Utopia for Realists (our review here), argues that we’re too moralistic about poverty. We tend to see people’s incomes as a function of their drive and intelligence (or lack of those things). But plenty of research shows the opposite: that people are poor, or lacking in intelligence, because of their circumstances.

That sounds like an anti-meritocratic or even anti-American thing to say. But Bregman points to studies showing that when people live in circumstances of scarcity–unable to pay bills and stressed out all the time about money–they run a cognitive “deficit” compared to richer peers. One experiment showed a decrease of 13 IQ points among participants facing severe financial difficulties. That’s the equivalent of failing to sleep at night or the mental gap between a chronic alcoholic and a moderate drinker.

To Bregman, this shows that low-income people can be more successful if we take away everyday burdens and that basic income should be seen less as a handout and more as “venture capital for the people.” “Poverty is not a lack of character. It’s a lack of cash,” he says.

Some estimates for the cost of a U.S. basic income put the cost at as much as $3 trillion a year, or 15% of total national income. That assumes paying every adult $1,000 a month regardless of their other income. But Bregman favors a form of means-testing through the tax code: what’s known as a negative income tax. People above the poverty line would continue paying taxes as they do now; those falling below the line would have their incomes raised via tax credits to a level that covers their essential needs. The idea has a long history. The libertarian economist Milton Friedman proposed one version in the 1960s, and the city of Dauphin, in Canada, implemented one between 1974 and 1979. It led to no decrease in employment, an uptick in the high school completion rate, and a reduction of hospitalizations and medical costs, researchers who studied the relevant data say.

Bregman is a little idealistic for some (many) tastes. He brushes over contrary evidence and argues that we already have “the research and the means” to implement a basic income right now, which we probably don’t. The Canadian experiment was 40 years ago and more modern experiments have taken place in India and Kenya, which may not be too relevant to the American context. (Current trials underway in Canada and Finland may yield more relevant evidence).

But then perhaps this is nitpicking. Bregman calls himself a utopian and utopians, for better or worse, don’t have to be accountants or rigorous social scientists. What matters to Bregman is the idea and that existing social programs have become moribund. “I’m a historian. And, if history teaches us anything, it’s that things can be different,” he says. “We need new ideas.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.