For years, it’s been easy to mistake Kickstarter for an electronics store.

It started when devices such as the Oculus Rift VR headset, Ouya game console, and Pebble smartwatch raised millions of dollars—far more than the creators even aimed to. Increasingly, Kickstarter is also used as a marketing tool for established companies to promote a new product, even when they don’t necessarily need a crowd to get the funds required to launch it.

Kickstarter is not trying to drive such campaigns off its platform, says Julio Terra, the company’s director of design and technology. But the crowdfunding platform, which started in 2009 as a venue to support artists and still cares deeply about enabling creativity, wants to be more than an electronics store. Unlike its best-known rival, Indiegogo, Kickstarter’s overarching goal is not to crowdfund anything and everything. In fact, its founders titled a 2012 blog post “Kickstarter Is Not A Store.”

“It’s not that we won’t work with them,” says Terra of the typical Kickstarter gadgets. “We will, but it’s not all that we care about.”

In early 2016, Terra formed a small team to help Kickstarter be more proactive in the kinds of projects it features. “We thought the most important thing was to create a framework where we could go out into the world and search for projects that we’re excited about,” he says.

Now that work has led to a new program called “Request for Projects,” which Kickstarter officially announced today. For the rest of 2017, the company is seeking endeavors that advance one of three things: scientific discovery, innovative design, or new tools (like novel musical instruments) that enable creativity. If it gets the results hoped for in tech and design, Kickstarter may extend the Requests for Projects approach to other project categories.

Requests for Projects items aren’t charity efforts. Kickstarter still takes its 5% commission on money raised, but it provides extra help like advice and promotion. “There’s a number of ways we celebrate projects on Kickstarter,” says Terra, “everything from newsletter [mentions] to staff picks.”

Kickstarter could make a lot more money if it focused on promoting consumer-oriented products, especially ones from established companies, but it’s no longer under pressure to do that. In late 2015, it became a public benefit corporation, or B corp, a type of company with a stated goal of increasing social good as well as making money. Requests for Projects aims to help ensure that this goal is reflected in some of the high-profile campaigns that show up on the site.

Not Your Typical Gadgets

“A project like mine, I wouldn’t have thought it had any place to be on Kickstarter,” says 27-year-old Kuwaiti artist Kawther Al Saffar. “What sells and what’s popular is stuff that’s tech-based and very consumer oriented.” Al Saffar studied at the Rhode Island School of Design and completed her masters degree at the Royal College of Art in London. Her thesis project—which literally came to her in a dream—is called Dual Bowls. Two metals, such as copper and zinc, are poured together in a mold to form rough-hewn metal bowls. “It’s temperamental. The results are always different,” she says.

Heather Corcoran, a member of Terra’s team in London, happened upon Dual Bowls at the Royal College of Art degree exhibition as well as the London Design Festival. She recruited Al Saffar to bring her idea to Kickstarter. The Dual Bowls project, which launched today, aims to raise 40,000 Pounds (about $50,000) to manufacture up to 1,000 bowls and get Al Saffar’s business up and running in Kuwait for more projects.

Request for Projects will include gadgets, but not always typical consumer-focused ones. Based in San Francisco, Clarissa Redwine hunts down especially innovative tech and science projects. The 26-year-old was previously program manager at chipmaker Qualcomm’s (now defunct) Robotics Accelerator before joining Kickstarter in January 2016. “I hop up and down the West Coast looking for these interesting projects,” she says.

The already high-energy Redwine becomes more animated when describing one of the projects she scouted, Foldscope, which she stumbled across at the science-focused co-working space Manylabs in San Francisco. Created by Stanford professor Manu Prakash, it’s an origami-like microscope that costs about $1 to make. “You fold it all together, and it has a little slide and a little lens, and it’s waterproof so you can take it outside,” she says. Foldscope hit its $50,000 funding goal in just three hours.

Other devices are far pricier. Wazer is a $5,999, desktop-size water-jet cutter. Starting from digital design, it directs a high-pressure stream of water mixed with abrasives to cut through materials ranging from glass and fiberglass to stainless steel and titanium. Wazer–an example of the sort of project the Requests for Projects effort hopes to encourage in the future–raised $1,331,936, more than 13 times its $100,000 goal.

Wazer uses a high-pressure water jet to cut materials like metal or tile into precise, intricate shapes.

Kniterate, another such project, does something similar with fabric: It’s a compact industrial knitting machine that manufactures items like sweaters and dresses based on digital designs. Terra stumbled upon the Kniterate creators at a London meetup in 2015 and helped them develop their Kickstarter campaign. Both Wazer and Kniterate fit into Kickstarter’s new mission because they are devices that enable people to create new things.

Different Kinds of Exploration

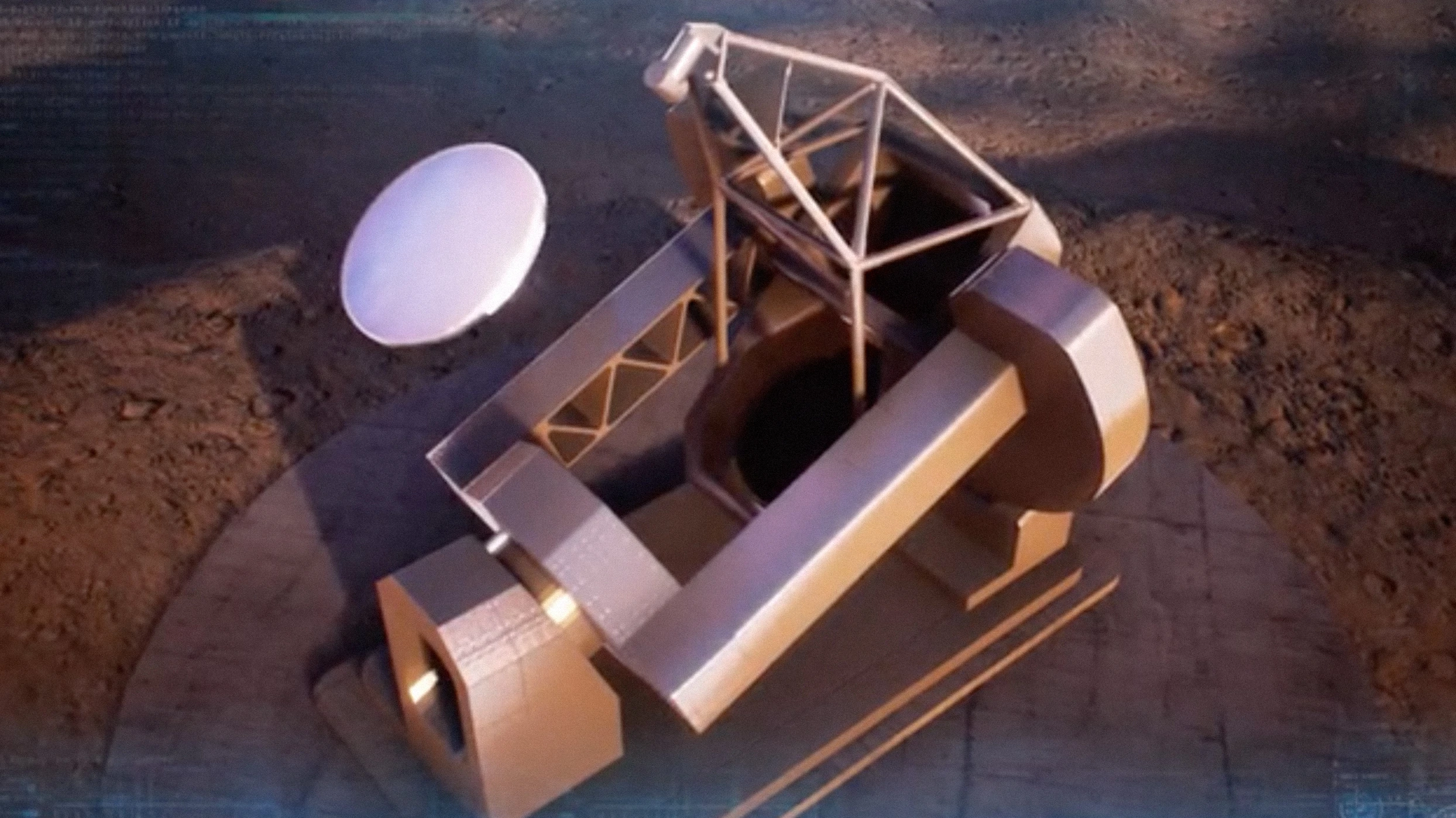

Not all of Kickstarter’s choice projects are for sale. On April 17, a Kickstarter for the PLANETS Telescope launched. A collaboration of six universities planned for the Hawaiian island of Maui, the PLANETS Telescope is designed to analyze the atmospheres of exoplanets outside the solar system for chemicals indicating the presence of life. (Its name stands for Polarized Light from Atmospheres of Nearby ExtraTerrestrial Systems.) “It’s a full analysis so we can say, yeah there’s a vey strong possibility that there’s life here,” says Kevin Lewis, the fundraiser for the project.

The universities and some large donors have raised about $3.5 million of the $4 million to build their first telescope at a defunct research facility atop Maui’s 10,000-foot Mount Haleakalā volcano. The Kickstarter’s $20,000 goal will go toward one part of the device—completing the primary mirror that magnifies the incredibly faint light filtered through the atmospheres of planets that are several light years away. It’s also a way to get the word out.

“We’re going to Kickstarter to start talking to a different audience,” says Lewis. “Instead of just the scientific and academic community, we want to include everybody in this.” If the project collects enough money for the mirror, it will add what’s called stretch goals, says Lewis, such as raising money for the structure that supports the telescope. Though the PLANETS Telescope is not a product, the organizers did create one for donors giving $110 or more: a glass cube with laser-engraved images of 25 potentially habitable worlds.

Kickstarter didn’t recruit the PLANETS Telescope as it did with Golden Bowls. Lewis already knew he wanted to raise money on Kickstarter, but he was surprised how excited the company was to work with him. After emailing Kickstarter to resolve a few questions, he heard from Redwine, who said she wanted to help with a custom campaign strategy. “I had a layout already, and they recommended like 40 different things I should change,” he says. “They were giving feedback on video and just the whole aspect of it.”

Now that Kickstarter is a B-corp, “as we craft our strategy, we know that our sole metric is not driving profit, it’s having an impact, you know driving communities,” says Terra. Community is a key aspect of Kawther Al Saffar’s Dual Bowls project. While her goal is to establish a company, she’s not picking the easiest place to do it. Building a business is already challenging for a woman in a traditional Muslim country, and building one based on handcrafts is even more challenging in Kuwait. “People don’t necessarily have an understanding or value for craft. There’s no financial incentive for craftsmanship to grow,” she says, since the oil-rich nation can import anything it needs. Al Saffar is challenging that trend, as well as segregation in her country.

Dual Bowls combine two semi-precious metals in one casting.

If things are manufactured in Kuwait, it’s probably by the hands of the foreign workers who outnumber Kuwaitis. To find metalworkers, Al Saffar says she wandered down back streets of Kuwait City until she came across a small foundry using a traditional Egyptian technique of casting metal with molds made from Nile River sand. Two Egyptian men manage the foundry, which employs foreigners from Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

Al Saffar describes Dual Bowls as an ad-hoc collaboration. She’s working with both local craftsmen and friends who contribute services like photography and web design. Al Saffar’s hoping to encourage a nascent creative spirit among Kuwaiti millennials. “For my generation, they’ve had this very pampered experience,” she says, “and now people are trying to break out of that and do something better with their lives.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.