For refugees escaping conflict in the Middle East and elsewhere, simply communicating with people in new countries can be a big challenge.

Groups helping refugees in Canada and the United Kingdom have found language barriers make it harder for newcomers to integrate into society and find work. And even in some refugee camps, aid workers who speak the same language as the people they’re there to assist can be in short supply, says Abubakar Abid, one of the cofounders of Tarjimly, a new Facebook Messenger bot designed to connect refugees and people assisting them on-site with volunteer, real-time translators who might be somewhere else on the globe.

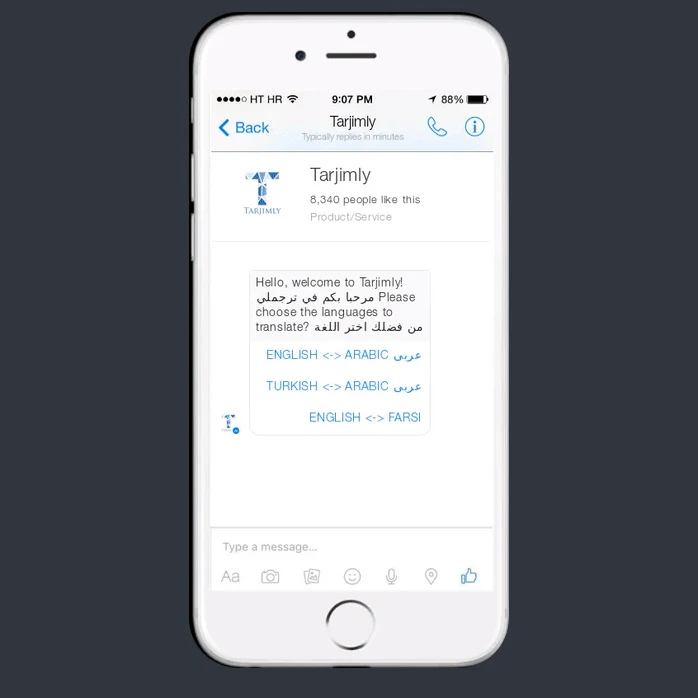

“All they do is message the [Facebook] page and they are routed to whatever translator is available in the language they are seeking,” Abid says. “They can send text messages, snippets of text, voice notes, pictures, or whatever media they like.”

Tarjimly’s cofounders, who are Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni, were inspired by a friend’s experience volunteering at a camp in Greece. “He went there expecting to help with operations or logistics,” Abid says. “He actually spent more than 90% of his time serving as a translator because he happened to be able to speak both Arabic and English.”

The founders announced the project January 30 and have since received sign-ups from more than 1,500 volunteers interested in serving as translators. They plan to test the tool with small groups of translators and users over the next few weeks and aim for a wider release in early March. They’re also exploring options for funding, including accelerators and incubators focused on social enterprises. Abid believes that using the Facebook platform to handle message routing should make it easy for the app to scale.

Tarjimly is just one of many apps and digital tools aiming to help refugees communicate, navigate, and find resources as they make their way in unfamiliar places. While refugees often leave their homelands in haste with limited possessions, those traveling from Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East have typically made sure to bring mobile phones. They’re often packed in a waterproof bag alongside identity papers, says a journalist based in Germany who operates the online directory AppsForRefugees.com under the pseudonym “John Tucker.” He says he adopted the name to avoid online harassment from anti-refugee trolls.

And since refugees began arriving in large numbers in Europe, software developers have sought to build apps to assist them. Tucker says the most visited apps from his site have included phrasebooks and dictionaries. Other popular apps include those that connect refugees with people who are offering items like furniture and household items and another that puts them in contact with locals looking to cook meals together.

“The people [arriving] here in Germany had no idea how to deal with authorities, with daily life, with the language, and so on,” Tucker says. “There are lots of apps on the market and websites which try to fill these gaps to connect these people with each other and give them some information about the country they’re in.”

In the United States, aid to refugees took on new urgency for some activists after President Donald Trump’s executive order, now blocked by a federal appellate court, banning new refugees and people from seven majority-Muslim nations.

The London-based makers of the Refugee Aid App, which catalogs assistance available to refugees in particular areas, quickly deployed the app in 19 U.S. cities after Trump’s order went into effect. “Our whole team just kind of worked round the clock to call these different organizations in these cities where there were airports where people were getting stranded,” says Shelley Taylor, CEO of Trellyz, the company behind the app.

The app, also known as RefAid, provides a menu of assistance, from legal advice to nearby health care. Taylor and her colleagues wanted to make sure that information on legal support would be available to refugees stranded in U.S. airports, provided they had time to access their phones before being detained. “We wanted to make sure that they could make phone calls to local organizations to get legal help before too many bad things happened to them,” she says.

Trellyz works with aid organizations around the world to help spread the word about their offerings and to assist them in digitally coordinating with each other. The company also relies on those same organizations to inform potential refugee users about the app’s existence. According to an October blog post published by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR), many refugees prefer to receive information from speaking directly to aid organizations, rather than from digital sources, especially with legal issues and other factors in flux.

That’s especially true after some apps released in haste during refugee crises reportedly failed to deliver on their promises, which AppsForRefugee’s Tucker acknowledges can be an issue. “It’s not always clear where these apps come from, and the quality is very diverse, let’s say that,” he explains.

But developers willing to ensure that their offerings actually match the needs of refugees and the people working with them can still make a difference, according to the UNHCR post.

“There’s also just an incredible desire of people around the world to help refugees,” says Abid. “And I think being able to tap into that is very, very valuable.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.