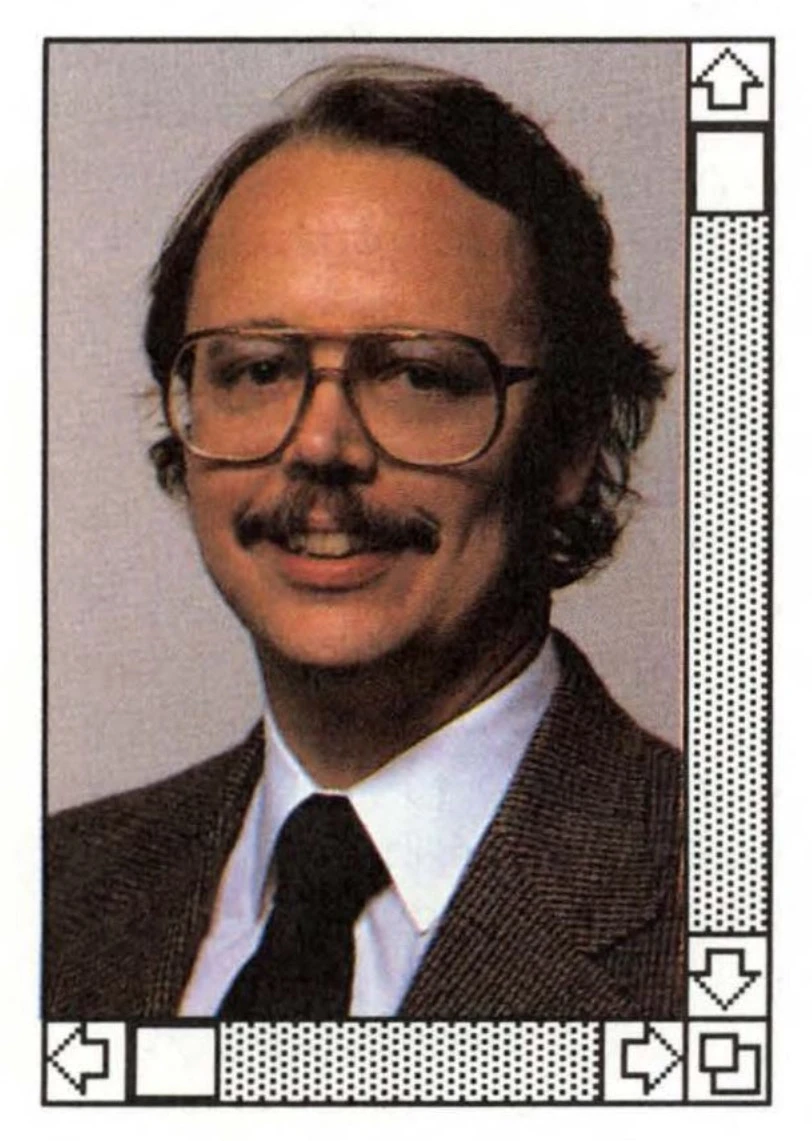

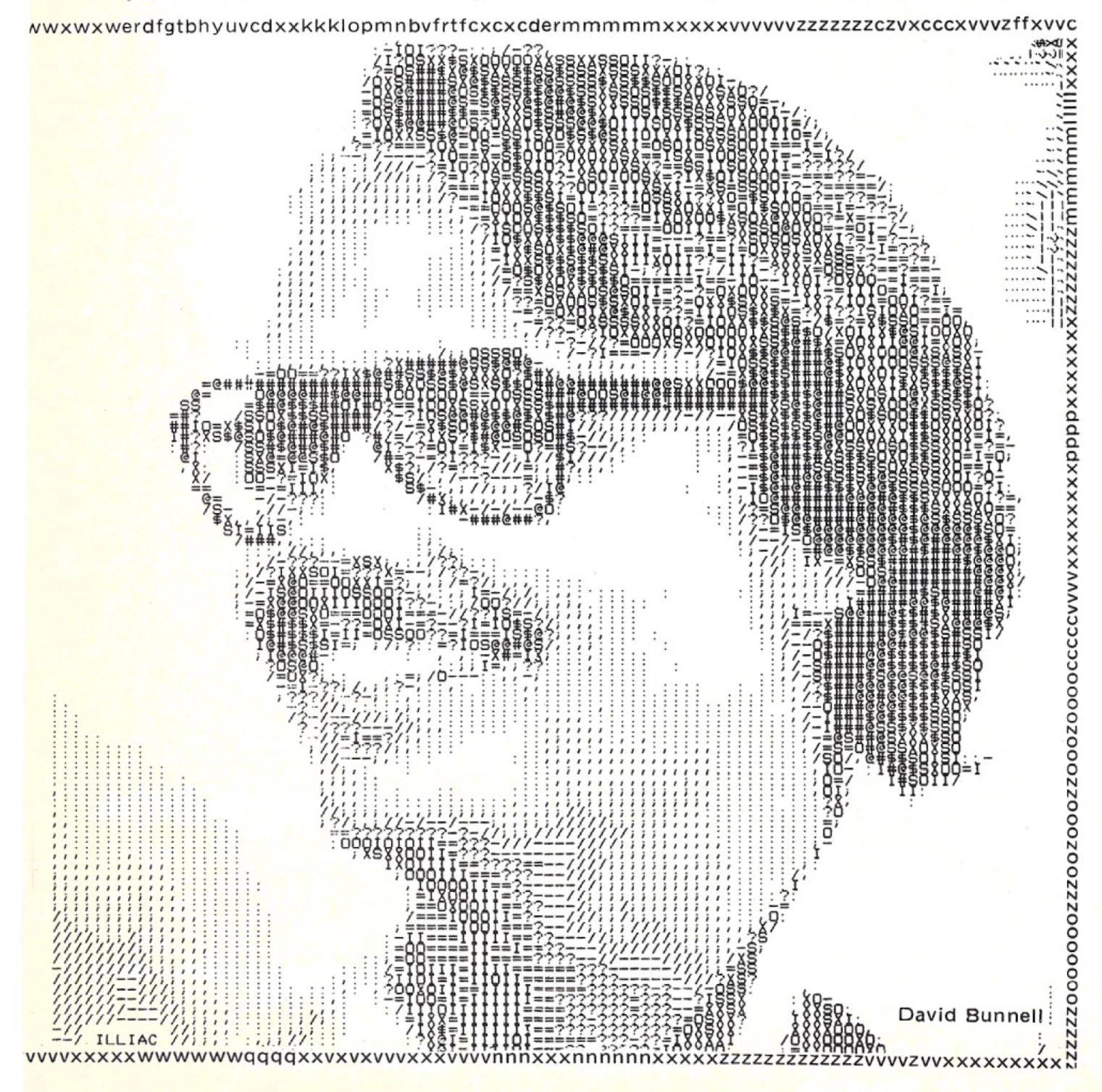

In 1973, a former schoolteacher named David Bunnell got a $110-a-week job as a technical writer for a tiny Albuquerque-based maker of calculators called Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems, Inc., or MITS. In later years, he admitted that he knew virtually nothing about electronics at the time. But he was there in 1975 when MITS introduced a microcomputer, the Altair 8800. The machine kicked off the PC revolution, including inspiring two budding computer nerds named Bill Gates and Paul Allen to write a version of the BASIC programming language, which led to them founding a company they called Micro-Soft.

Starting in April 1975, Bunnell edited MITS’s newsletter about the Altair, Computer Notes–a periodical that, as far as I know, was the first devoted entirely to the subject of personal computers. He went on to start Personal Computing, one of the first slick magazines on the topic. Then he cofounded both PC Magazine and PC World, the Coke and Pepsi of PC publications. And then Macworld–both the magazine and the trade show. At one point, four of the top 10 computer magazines were ones he’d started, and PC Mag, PC World, and Macworld are all still very much with us in online form.

Bunnell died on Tuesday evening at his home in Berkeley, California, at the age of 69. I worked at PC World for 13 years, and though I arrived years after he left, he was an inspiration to me in ways that went far beyond him having created the publication that gave me a livelihood. Above all, he was a guy who saw technology as a tool for human beings.

Student, Activist, Teacher

David Hugh Bunnell was born in Nebraska in 1947. That meant he came of age in the 1960s–which he did by, among other things, founding the Nebraska chapter of the activist group Students for a Democratic Society; leading a 4,000-person march on City Hall to protest discriminatory housing in Lincoln, Nebraska; attending the trial of the Chicago Seven; and participating in the massive 1969 anti-war protest in Washington D.C.. (He also found time, in his senior year at high school, to serve as sports editor at the newspaper where his father worked.)

After graduating from the University of Nebraska, Bunnell worked as a teacher in Chicago and then relocated to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where he smuggled food to the Native Americans who occupied the town of Wounded Knee during a 71-day armed standoff in 1973. (Before his death, he completed a memoir of his Pine Ridge days, Good Friday on the Rez, for publication next year.) From there, he moved to Albuquerque and stumbled his way into the computer industry by answering MITS’s want ad in a local paper.

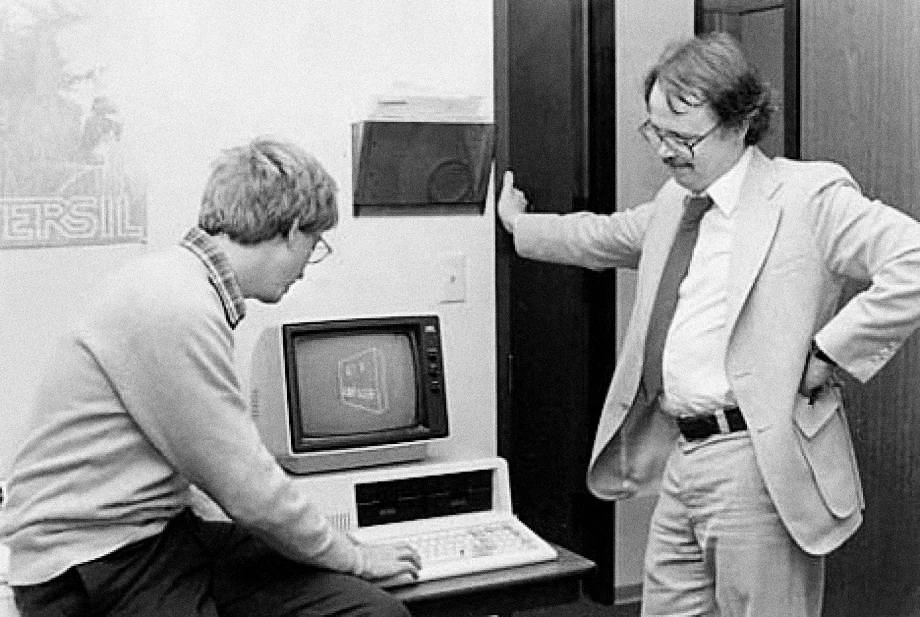

At MITS, he produced documentation, started the Computer Notes newsletter, and presided over the 1976 World Altair Convention, the first conference for PC users. That put him smack at the center of an industry that started out minuscule, but just kept on growing. (He even helped Microsoft put together its very first ad.)

In 1977, Bunnell devised the idea for Personal Computing magazine and convinced Benwill, a Boston-based publisher, to fund it. Less geeky than Byte, the biggest computer monthly of the time, it was a template for many mass-audience tech magazines that Bunnell and others would found in the years to come. He even got his former MITS colleagues Bill Gates and Paul Allen to write a software column for it.

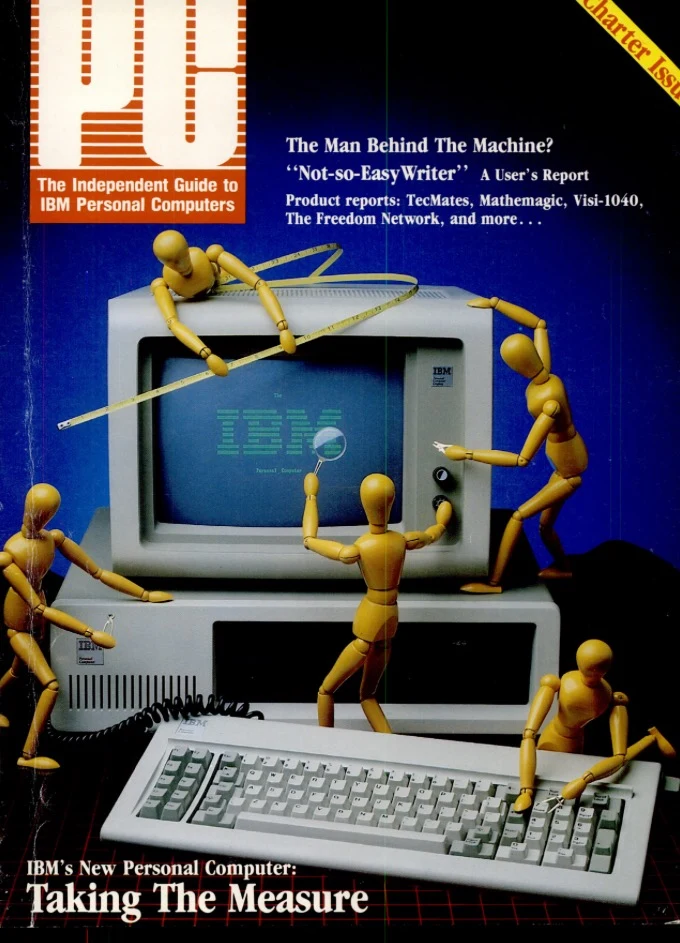

Bunnell wanted a share of ownership in Personal Computing; when Benwill wouldn’t give it to him, he walked after just a few issues had been published. (The magazine continued on without him, quite successfully, into the early 1990s.) He relocated to San Francisco and, after a brief period working as a word-processing operator, became managing editor at the book-publishing firm founded by Adam Osborne, who would later be best known for his eponymous portable computer. When IBM announced its first PC in 1981, Bunnell, Osborne colleague Cheryl Woodard, and Jim Edlin were inspired to found a magazine devoted entirely to the new computer and its ecosystem. With a staff of six (including Bunnell’s wife Jacqueline Poitier, who survives him) they put together the first issue in a spare bedroom at the Bunnell home.

That magazine–PC Magazine–was such a success that multiple large publishing companies were soon interested in acquiring it. In fact, Bunnell and Woodard thought they’d struck a deal to sell it to Pat McGovern of IDG, publisher of Computerworld and InfoWorld, when they learned that their financial backer had sold it to Ziff-Davis without bothering to tell them. They–and 48 of the magazine’s 52 staffers–responded by promptly quitting to found PC World for IDG. Its first issue was so thick with advertising that it set records.

With their next major IDG launch, Macworld, Bunnell and Woodard perfected the art of hitching a media brand to a computing platform. Thanks to a deal Bunnell hammered out with Steve Jobs, the magazine debuted on January 24, 1984, the same day as the Mac itself, and was promoted directly to new Mac owners via materials that shipped with the computer.

In 1985, Macworld the magazine spawned Macworld Expo, one of the few successful tech conferences ever aimed at consumers rather than industry types. By the time I started going circa 1988, it was held on both coasts and the Boston edition, which I attended, filled two convention centers. Still later, well after Bunnell was no longer associated with it, the San Francisco version made front page news each year as the venue that Jobs used to announce products such as the first iPhone.

The thing that made Bunnell intriguing rather than merely successful was that he never stopped thinking like a 1960s social activist, even after he became a tie-wearing publishing magnate. In 1986, for instance, he published a blistering editorial in PC World and Macworld decrying Georgia’s sodomy law as being a violation of the spirit of the PC revolution–a bold decision given that the state was, at the time, home to numerous major companies in the industry, some of whom yanked their advertising. The move led the Fund for Human Dignity, an LGBT rights organization, to honor him with its Howard J. Brown Award.

“The overwhelming thrust of the personal computer is that it can liberate and empower people,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1987. “Unfortunately, so far it has largely been a white males’ revolution.” Publishers of trade magazines are not exactly known for talking like that.

Bunnell left IDG in 1988. His many subsequent ventures didn’t attain the name-brand status and longevity of a PC Magazine or Macworld, but included such inventive ideas as BioWorld (a biotech publication sent by fax at a time when that was cool) and ELDR (a magazine for active, affluent people over the age of 60, which happened to be the age David had reached when he started it). He also founded Computers and You, a computer-skills center in San Francisco’s notoriously hardscrabble Tenderloin neighborhood.

As a long-time computer magazine junkie who began working at PC World starting in 1994, I was well aware of Bunnell’s importance to the industry I worked in. But I didn’t meet him until we began planning the 20th anniversary issue of PC World, which appeared in early 2003. My boss, editorial director Kevin McKean, asked him in to have lunch and talk about the old days–an invitation of some significance given that our cofounder’s departure from IDG had been followed by years of legal tussling between him and the company.

When we gave Bunnell an impromptu tour of our editorial offices, he told us that he hadn’t been back since leaving the company 14 years earlier. I still remember our head of human resources, who’d been there when Bunnell left, coming across us in a hallway and looking dumbstruck to see him back on the premises.

After that, I ran into him every so often, usually in interesting circumstances. Once year, we ended up standing next to each other in a sea of people waiting to get into a Steve Jobs keynote at Macworld Expo, with him casually sharing tales of what it had been like to start the whole thing. Another time, we found ourselves seated at the same table at a New York awards banquet where ELDR was being honored.

When I wrote about subjects such as the passing of MITS founder Ed Roberts, the rise and fall of Adam Osborne, and the history of the BASIC programming language, I would interview my friend David, who had witnessed so much history. He added me to the mailing list for his poems on topics such as the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 March on Washington.

The last several times I saw him were at benefits held in conjunction with the Andrew Fluegelman Foundation, which was named for the late founding editor of PC World and Macworld. Founded (and funded) by Bunnell, the organization provides college-bound students from underprivileged backgrounds with MacBooks. He was a twinkling, giddy presence at these events, taking palpable joy in giving away computers to people who really needed them. For all the other accomplishments he packed into his life, I can’t imagine a better way to remember him.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.