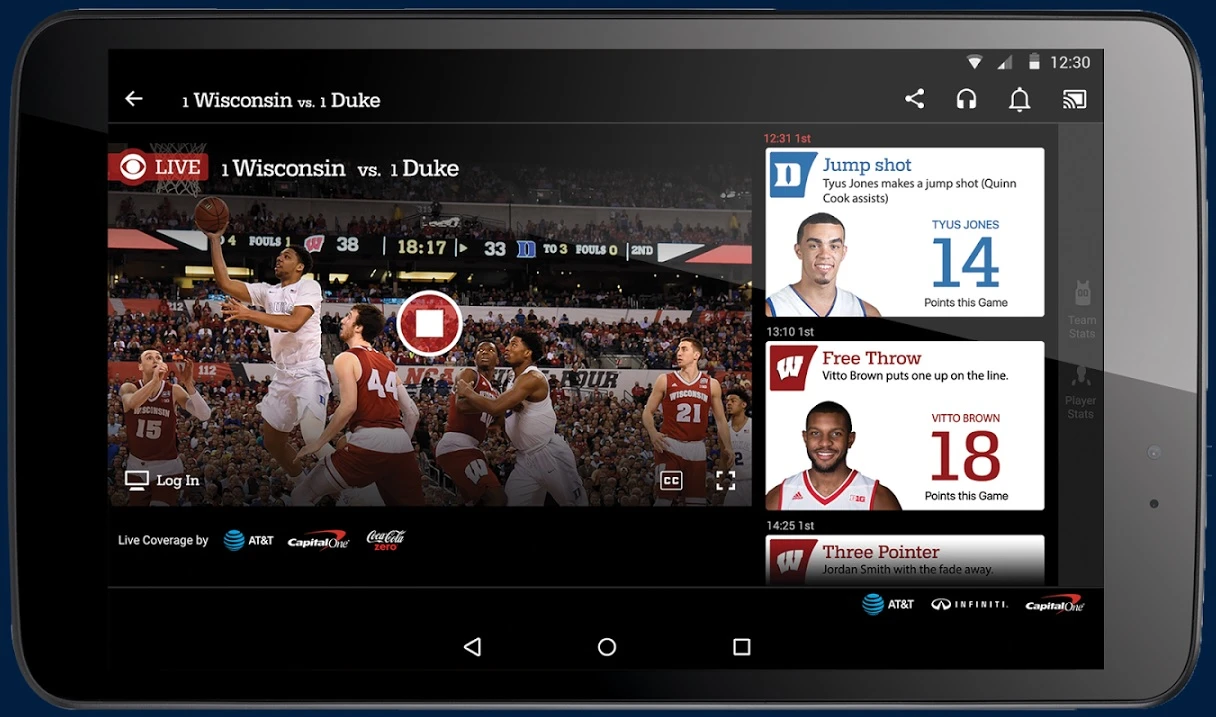

If this year’s March Madness is anything like the last, viewers who opt to stream the late-round games over the Internet should brace for some unpleasantness.

Streaming is notoriously finicky during major live events. This year’s Super Bowl had problems, as did the Grammy Awards and the Oscars. And last year, March Madness proved disastrous for Dish’s Sling TV streaming service, as a swell of trial members were unable to tune into the Final Four. The evidence goes beyond mere anecdote: Streaming optimization firm Conviva estimates that 15% to 30% of all video on the Internet involves some sort of bad experience. Live streaming tends to get hit the hardest.

When things go wrong, streaming providers are quick to offer convenient excuses, such as unprecedented levels of demand. But these mea culpas don’t tell the whole story, and obscure the fact that when a live stream fails, it often comes down to money and pride.

A Thousand Points Of Failure

When I first started researching this story, I assumed that live streaming’s issues were caused by some fundamental technology constraint. Streaming providers so often blame their problems on bandwidth that it’s easy to believe Internet technology can’t keep up with the demands of modern viewers.

But Dan Rayburn, a streaming video analyst at Frost & Sullivan, argues that live streaming at scale is more of a business challenge than a technical one. When a live stream runs into trouble, he says, a lack of bandwidth is almost never the culprit.

More often, streaming services don’t plan enough for all the other things that can go wrong. Rayburn points out, for instance, that CBS’s recent Grammy stream had an issue with verifying users’ locations. Last year, NASA blamed problems with its Mars live stream on a chunk encoding issue with content delivery network Akamai. Apple owed its live stream failure in September 2014 to a snafu in how the company set up its content on Amazon’s servers. And CBS’s 2016 Super Bowl stream had an issue with the video player on Apple TV, which the network still hasn’t fully explained.

“That’s the problem, is single points of failure with a lot of these things,” Rayburn says. “When a backup doesn’t kick in, or you don’t have it, or you haven’t planned for it, or you don’t want to spend the money for it, well, your live event’s going to go down.”

Why not invest in making sure everything runs smoothly? Rayburn argues that the rights to stream major live events are so expensive that no one wants to pay more than necessary just to ensure an error-free streaming experience.

“The biggest solution to keep these issues from happening is simple: Redundancy,” Rayburn says. “But in order to have redundancy, you have to spend a lot more money to put all the redundancy in place, which many companies are not willing to do, because they’re already not making money on live events.”

Even if media companies do make the necessary investments, it’s impossible to plan ahead for every outcome. That’s why It’s just as important to actively manage the network on the day of the event, says Adam Cahan, Yahoo’s senior vice president of video. Right now, Cahan doesn’t believe major media companies are putting in that kind of effort.

“It requires a level of sophistication,” Cahan says. “I’ve not seen that from–call it a more traditional media kind of company–I’ve never seen that level of sophistication.”

Playing The Blame Game

When things do go wrong, it doesn’t help that there’s a shortage of accountability for all the players involved. As Rayburn points out, streaming providers are eager to point out how many viewers tuned into a live-streaming event (see CBS boasting of 1.4 million Super Bowl 50 viewers) but less forthcoming about the quality factors such as start time, buffering, and dropped packets.

“If you showed up, and had a crappy experience, it doesn’t matter that you showed up,” Rayburn says.

The good news is that the industry is starting to talk more about measuring quality of experience. But right now, there’s little agreement on what those measurements should look like, says Keith Zubchevich, chief strategy officer at Conviva, a company that helps media companies optimize and monitor their streaming services.

“If somebody says, ‘I drink five beers a day; I don’t have a drinking problem because my uncle drinks 10,’ then we both have a problem,” Zubchevich says. “It can’t be relative, it’s got to be the same.”

This lack of consistency is likely a symptom of a finger-pointing problem that runs rampant in streaming video, Zubchevich says. When March Madness viewers start griping about a stream on Twitter, the provider might just pass the blame onto the content delivery network, which might blame the Internet provider, which might blame a particular device’s video player. In the end, no one wins.

“Everybody’s great, no one’s bad,” Zubchevich says. “So if there’s a buffering problem, it wasn’t me. And if there’s no problem, it was me.”

Time To Fess Up

Fortunately, the industry is finally starting to behave like it wants do better. In 2014, a bunch of big players formed the Streaming Video Alliance, with the goal of devising best practices for live streaming and standardized ways to measure the experience. The group counts Comcast, Fox, MLB Advanced Media, and Yahoo among its founding members.

The hope is that by agreeing on how to measure problems like buffering and congestion, the various links in the chain can do a better job of preventing those failures from happening and owning up to any mistakes.

“We don’t need teleportation or levitation to be solved to do what we need to do,” says Mark Fisher, vice president of Marketing at streaming-optimization firm Qwilt, another alliance member. “But we do need cooperation and collaboration within the ecosystem, and a commitment across the board to deploy the infrastructure needed to do this.”

It might seem a bit hokey to point to an industry standard as the solution to all of its ills–especially given the problems that such efforts can run into–but at least the industry is showing a willingness to improve.

As for what took so long, Fisher points out that major media companies have spent decades relying on a broadcast system that was much simpler and more reliable, only to find just recently that everything’s changed in the age of Netflix, Hulu, Apple TV, and Roku. Having to suddenly become well versed in a more complex streaming ecosystem is sort of like swapping an airplane’s engine in mid-air.

“This is happening to the industry,” Fisher says. “This is not the industry really driving an outcome…It really just happened, and now it’s a force of nature.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.