Is Uber even part of the sharing economy? Does Airbnb’s business model have a positive or negative impact on communities? Are on-demand startups like TaskRabbit leveraging exploitative business models? What is the right approach for local governments when it comes to regulating the sharing economy?

These are just a few of the persistent questions regarding the new range of businesses reshaping our business landscape. Some prefer to see the world as black and white: “Sharing will save the world by reducing our environmental consumption while solving income inequality” versus “sharing platforms are really just a share-washing platform version of capitalism for the 1%.” But in reality, the emerging sharing landscape is very complex.

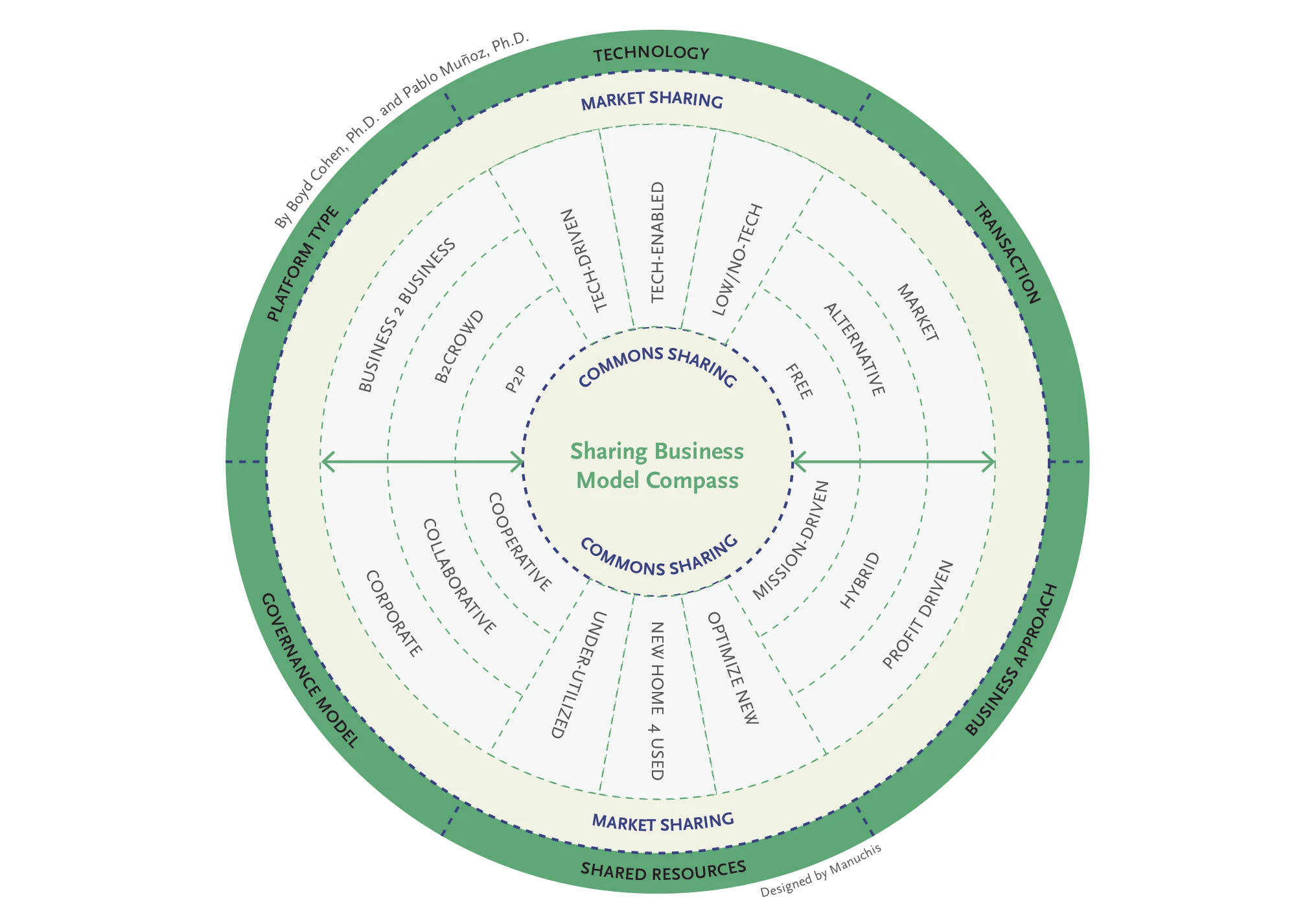

To begin to get under the hood of the business models of sharing-economy players, my colleague, Pablo Muñoz and I analyzed hundreds of sources of data on 36 different sharing business startups representative of Jeremiah Owyang’s Honeycomb model, a graphical depiction of the different sectors where sharing startups have gained traction. While the Honeycomb model has been of great use in framing the diversity of sectors being impacted or disrupted by the sharing economy, it does not provide any insights on the underlying business models across the 12 different sharing-economy sectors that Owyang identifies. So we identified six key dimensions of sharing-economy business models, each of them with three distinct decisions that can be made by sharing startups. We converted this into what we hope is a useful tool, the Sharing Business Model Compass.

Four of these dimensions–transaction, business approach, governance model and platform type–offer business model decision choices roughly on a continuum from more market-based sharing (i.e. platform capitalism) towards commons-based sharing (i.e. platform cooperatives). While the other two dimensions–technology and shared resources–have decisions relatively agnostic to market or commons orientations.

If you’re thinking of starting a sharing-based business, we believe this tool is useful in demonstrating that there are a plethora of key decisions unique to the sharing economy that entrepreneurs must make along the way. If you’re thinking about the sharing economy in general–and how it interacts with people, government, and the world–this framework can be helpful in explaining what specific parts of the sharing economy you find optimal–or objectionable.

Technology

Within this dimension, there are three choices: tech-driven, tech-enabled, and low/no-tech. Tech-driven business models are ones leverage technology not just to connect users but also to complete the transaction without the need for offline interaction. Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo and online learning portals such as Udacity and Coursera fall in the tech-driven category. The majority of the startups we studied fall more in the tech-enabled category, which represents business models reliant on technology to facilitate the connections but require or are enhanced by offline interactions. Uber would fall into this category, as would Wallapop, a fast-growing hyper-local mobile classified business for P2P reselling of used goods. While most of what we think about in the sharing-economy space is at least enabled by technology, there are still many startups in the sharing space where technology is at most a supporting-tool but not critical (i.e. low/no-tech). Co-working spaces and shared commercial kitchens are good examples of the low/no-tech business model, while other models such as the Repair Café are hyper-local, nonprofit, no-tech sharing actors.

Transaction

We observed three variations in transaction types: market, alternative, and free. Perhaps the most extreme version of market transaction is Uber, which does not only vary pricing based on demand, but also includes the highly controversial surge pricing. Most of the scaled, venture capital-backed sharing startups–such as Airbnb and Rent the Runway–opt for market pricing. The alternative option is jut starting to emerge. While there are perhaps fewer scaled examples so far, Bliive, a rapidly globalizing time bank out of Brazil is a good example. Instead of on-demand models that seek to facilitate economic transactions between a service provider and a home-owner, time banks allow service providers to earn “time dollars” to be exchanged later for other service provided at a later date from someone else in the community. Yerdle, a P2P service for exchanging used goods also falls into the alternative category. Instead of exchange for cash, users earn Yerdle dollars for acquiring other goods in the future. Peerby, another P2P used goods exchange, founded in Amsterdam in 2011, offers a completely free service. Of course, many bike-share services are free or just require an annual deposit. While you may think that free bike-sharing services have no business model, and perhaps are just subsidized public transit options, think again. Most of the scaled bike-sharing services in cities like Paris, Mexico City, London, and New York City, generate most of their revenue through sponsorships or advertising models.

Business Approach

There are three primary options from sharing providers with respect to the business approach: profit-driven, hybrid, and mission-driven. We consider Uber, Upwork and eBay to be amongst the many sharing platforms that are profit-driven. Profit does not have to be a bad word, however, and we do not believe a sharing firm that is profit-driven to necessarily be bad corporate citizens. But there are viable alternatives. Hybrid models are those that are usually founded as for-profits but have a clearly stated goal that drives them to create social and/or environmental benefits in communities. Zipcar, sold to Avis for $500 million is a good example as it was founded, and stayed true to the goal of reducing congestion and contamination in cities, while providing access to a vehicle for people who could not afford, or choose not to own one (or a second) vehicle. Kickstarter, at a minimum would also be considered a hybrid approach as they aspire to support creative projects around the globe and to be good corporate citizens. At the end of 2014, Kickstarter joined the growing group of responsible companies who became a certified B-Corporation, which obligates them to transparently track and monitor their sustainability performance. Kiva is even further down the path of a mission-driven company, having formed as “a nonprofit organization with a mission to connect people through lending to alleviate poverty.” Certainly the more than 1,000 Repair Cafes around the globe would fit squarely in the mission-driven category as well.

Shared Resources

In her book, Peers, Inc., Robin Chase (the founder of Zipcar) suggested that sharing business models optimize under-utilized resources in society. We agree, although as we studied the business models we realized that there are really three ways sharing startups seek to achieve this. They either optimize new resources, help find a new home for used resources, or leverage facilitate the optimization of under-utilized, existing resources. Zipcar itself is a good example of the optimization of new resources as more often than not their fleet is made up entirely of newly acquired vehicles. Rent the Runway actually started with a model focused on the optimization of under-utilized existing resources (e.g. dresses worn once to a wedding), but have shifted their model in recent years to the optimization of new resources where the company acquires new clothing for rental to users of their platform. Many of the P2P models for used items we already mentioned (e.g. Wallapop, eBay, Peerby), fall into the “new home for used resource” category. In the optimization of under-utilized resources category, P2P car-sharing and carpooling models like Blablacar fit well. Similarly, crowd-shipping models such as Shipizy also belong here.

Governance Model

The governance models for sharing startups range significantly, from traditional corporate structures to collaborative governance models to cooperative models. Corporate structures seem to be the choice, not surprisingly so, for most venture capital-backed business models in the sharing economy (e.g. Uber, Airbnb, Upwork, Rent the Runway). Yet some scaled sharing businesses such as Kiva embrace collaborative approaches to working with users and other stakeholders in sourcing, implementing, and monitoring projects funded through the platform.

While we found a relatively small amount of projects currently embracing collaborative business models, we expect this number will grow significantly over time, as the benefits to more engagement with users on the platform become more apparent. The cooperative governance model for sharing-economy startups, though, has yet to get much traction–although some of the components of cooperative models can be seen in alternative and cryptocurrency startups. Also, there are reports of taxi drivers in cities joining forces to form cooperatives in an attempt to respond to Uber competition. There is a big drive from within the sharing community to support more “platform cooperatives” as evidenced by the Platform Cooperativism event (and the numerous conversations and smaller-scale events since) which was highly attended in New York City at the end of 2015.

Platform Type

While we are used to thinking of the sharing economy as being peer-to-peer (P2P), in reality, there are at least three common platforms in use: B2B, business to crowd and P2P. In the B2B category you can find companies like Yardclub, founded by Caterpillar, which facilitates the rental of Caterpillar tractors for construction sites. Similarly, Cohealo facilitates the sharing of expensive hospital equipment between hospitals. In the Business to Crowd category, companies like Zipcar and Rent the Runway choose to own the resources that will be exchanged within the user community. And platforms where peers exchange products or services with each other, and where the platform provider owns virtually none of the shared assets (such as Airbnb, Task Rabbit, Indiegogo, Blablacar, etc.) fall into the classical P2P category.

Implications

As we have seen, in some cases, like Rent the Runway, business model choices may evolve over time in response to user experiences, profitability expectations, societal impacts, or investor preferences. Importantly, the compass demonstrates there is a lot of grey in sharing business models. In fact, if one assumes that all sharing business models contain the six dimensions addressed in the Compass, and that all sharing startups must choose just one option within each dimension, this leads to a total possible of 729 unique business models. That is to say, there is a lot of diversity within the sharing business and this diversity has potentially significant implications for the scalability, profitability, investability, and the social and environmental impact of users and communities as a whole.

We believe that sharing startup founding teams would be wise to discuss these decisions early in the formation of the venture.

We also believe that local and regional governments seeking to regulate the sharing economy would be wise to think through the underlying dimensions of different business models in order to develop more sound policy to encourage the type of sharing business models desired while disincentivizing or regulating elements that are least desired.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.