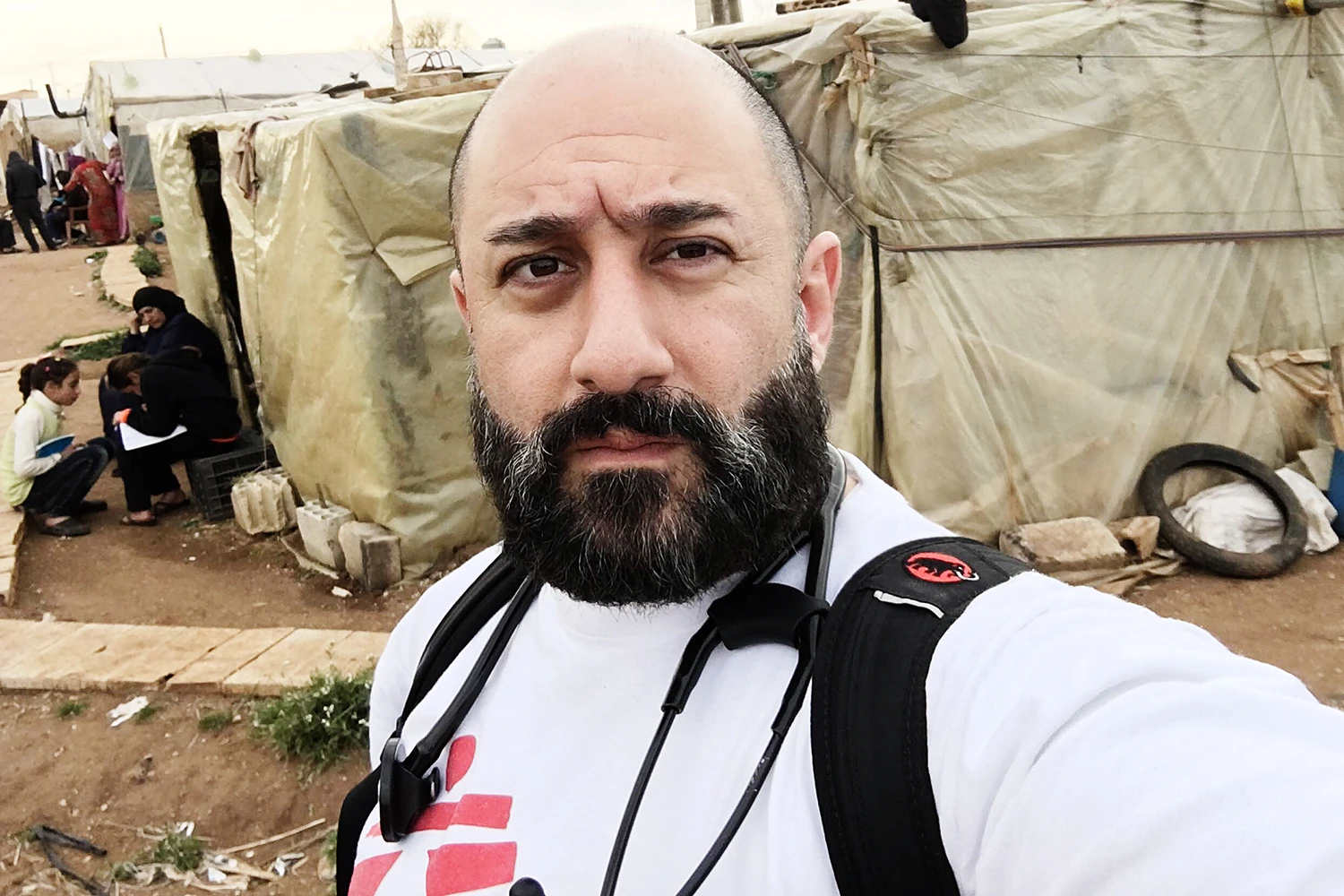

Dr. Rogy Masri is a doctor stationed at a settlement in Northern Lebanon. His team primarily treats Syrian refugees, who have flooded into Lebanon and other neighboring countries to escape escalating violence.

It’s not a job for the faint of heart; medications are in short supply, electricity routinely cuts out, and patients are suffering from all manner of horrible ailments from lice and rat bites to sexually transmitted infections.

Masri, who is a volunteer with Doctors Without Borders, must make do with limited tools and equipment. When a patient walks in with a common ailment, he can typically send them away with a treatment. But that’s not always the case.

In an interview with Fast Company, he recalled a refugee walking into the clinic with a furiously red skin legion about the size of a quarter on his hand. This patient had not responded to a previous course of antibiotics. Masri, who is not a dermatologist and has little experience with exotic diseases, was stumped.

He took out his smartphone and snapped a photo of the wound, which he uploaded to an app called Figure1. He noted in the caption that the patient was a 52-year-old male Syrian refugee with an infection that had been treated for a year. The patient experienced no pain or itchiness. The results of a biopsy were still “pending.”

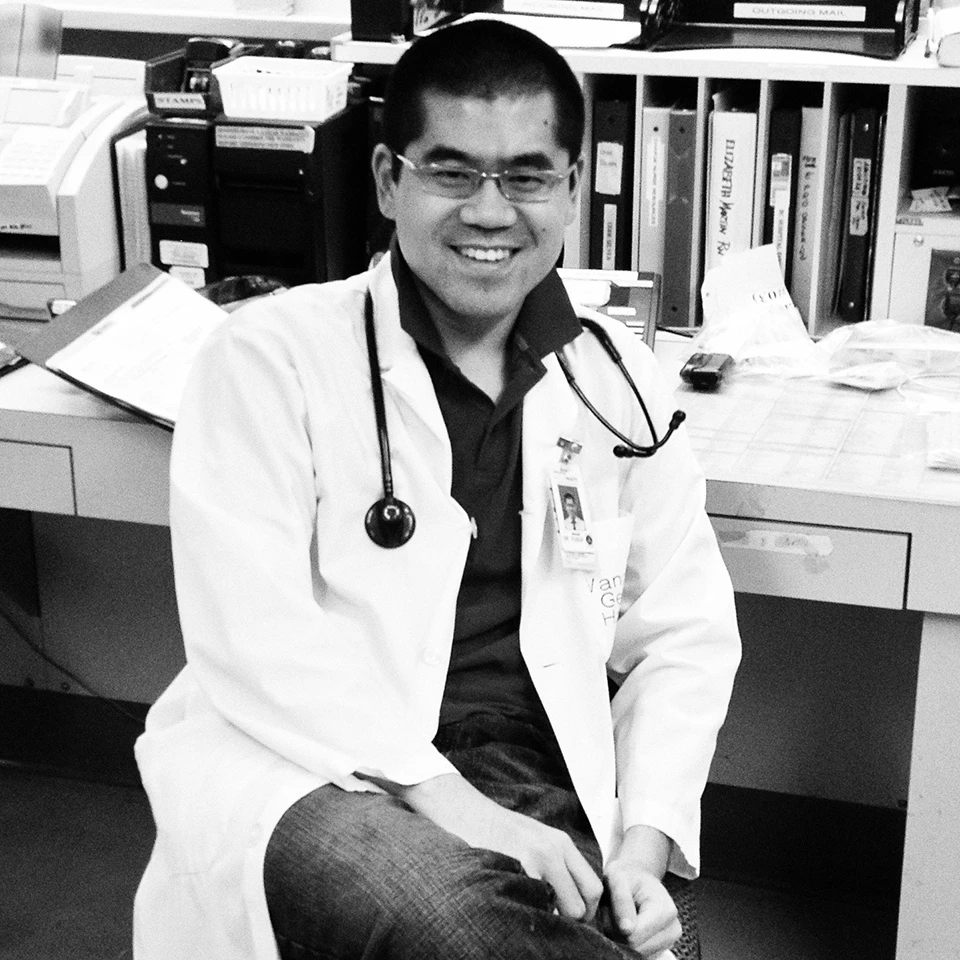

On that particularly day, Yusuf Dimas, an internal medicine resident at St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Canada, happened to come across the photo. He had a bit of free time between shifts, and decided to play medical detective. After ruling out a bacterial infection (the patient hadn’t responded to antibiotics) Dimas concluded that the patient was likely suffering from Leishmaniasis, which is fairly prevalent in refugee camps with unsanitary conditions.

“Even from across the globe, I can say with a high degree of certainty that it was that (diagnosis).” Dimas suggested that the patient get a course of drugs to treat the infection, while awaiting a biopsy result. He later learned that his hunch was correct.

The Rise Of Telemedicine

Telemedicine apps like Figure1 are radically transforming how patients are treated in the most under-resourced parts of the world. Telemedicine broadly refers to the practice of doctors evaluating, treating, and diagnosing patients in remote locations using technology.

In the United States, these apps are commonly used in rural areas that lack medical services and clinics. Worldwide, the use of telemedicine is expected to grow by more than 10 times from 2013 to 2018.

More than 1.3 billion people lack access to affordable health care today, and represent the majority of the world’s population suffering from serious medical conditions,” said Morgan Reed, executive director of The App Association. “Telemedicine tools that could improve this situation are available today at increasingly competitive prices around the world.” According to Reed, telemedicine will become mainstream when regulators remove stumbling blocks, and insurance companies figure out new models for reimbursement.

Figure1, which is colloquially described as the “Instagram for doctors,” has become a go-to option for health workers in underserved areas. The app, which launched in 2013, is the brainchild of a Toronto-based doctor named Joshua Landy. Figure1 boasts more than half a million users, including doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals.

“We see a lot of doctors post photos from areas with no comprehensive medical care,” says Landy by phone. “We have users in the military, in the jungle, and in refugee camps.” Landy stressed that patients can rest assured that their privacy is protected. After a user uploads an image to Figure1, it is wiped of any identifying details. And the servers contain no record of location information.

For Masri, his smartphone has now become an essential tool for fieldwork. When he needs a second opinion, apps like Figure1 and those developed by Doctors Without Borders connect him with medical professionals across the world on a real-time basis. The downside is that Internet service and electricity aren’t always reliable. Masri occasionally finds that Wi-Fi cuts out when he’s halfway done uploading a photo, which is a constant source of stress and anxiety.

That said, Masri describes telemedicine as “essential for treating Syrian refugees who don’t have access to specialist care, let alone the quality, regular follow-ups.” He routinely uses telemedicine apps to “rule in or rule out” diagnoses, particularly when he’s confronted with a rare disease that he’s never encountered before. “It’s like having a colleague in every part of the world to bounce ideas off.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.