Over the past several years, I have been witnessing a decidedly urban revolution in the world of entrepreneurship. Early research in entrepreneurial ecosystems assumed that the network of actors who contribute to entrepreneurial activity were regionally based. This is hardly surprising, given that Silicon Valley has been the beacon for economic development officers around the globe who seek to “replicate” a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem in their jurisdictions.

I consider this ambition quite foolhardy on so many levels. Firstly, Silicon Valley evolved in a very unique way, in close proximity to Stanford University and with the early growth of the semiconductor market, and Hewlett Packard’s emergence in the region. This is to say, it is impossible to replicate an entrepreneurial ecosystem in another region of the world because each ecosystem evolves in its own way with its own set of actors and sequencing that is difficult or impossible to control. Furthermore—and this is meant with no offense to anyone living or working in Silicon Valley—but it is not really all it is cracked up to be, particularly from an urban quality perspective. Silicon Valley is mostly made up of sprawling, monolithic warehouse buildings in a very car-dependent setting. This is no longer seen as an attractive environment for startups, both for their founders and for their future employees.

Richard Florida has been documenting, for example, the migration of venture capital investments from suburban tech parks into urban areas. In fact, this very phenomenon is occurring in the Bay Area: previously Silicon Valley-based tech companies, such as Twitter, have been migrating to San Francisco. Florida’s recent work has found that there is actually more venture capital investment in San Francisco than in Silicon Valley.

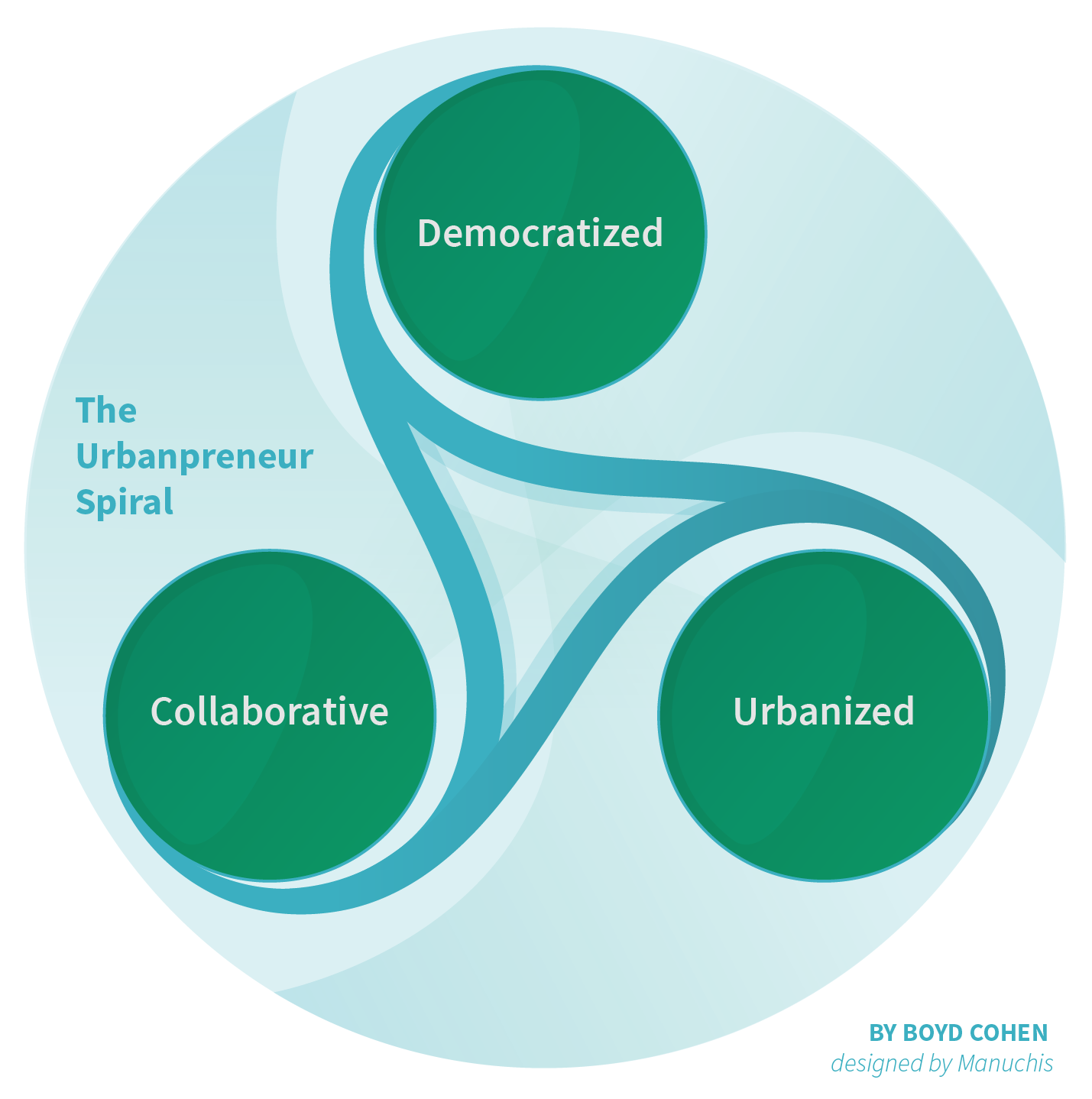

Entrepreneurship is increasingly becoming an urban phenomenon. There are three factors that are creating what I call the “urbanpreneur spiral.”

Urbanization

Urbanization of the world’s population is an unstoppable freight train. But what this means for entrepreneurship has been underexplored. Naturally, if more of the world’s population is in urban areas, we could assume more entrepreneurs will be in cities, as well. But urbanization means more than just more people and entrepreneurs living in cities. Urbanization brings with it massive challenges for cities. People are moving to cities because they believe there are more opportunities and a better quality of life for them and their families. Yet many cities around the globe are struggling to meet the growing expectations of the masses, such as public transit and transportation infrastructure, housing, jobs, food, access to green space and clean air, and so on. While this suggests added burden to local governments, it also has given rise to a new breed of civic entrepreneurs who seek to resolve quality of life challenges in cities with both hybrid and for-profit business models.

Collaboration

As entrepreneurs and established companies seek to help local governments innovate and meet the needs of their growing populations, new types of collaborations are emerging. In some cities, we are witnessing something I refer to as 5P partnerships (public-private-people-professor partnerships) whereby consortiums of local and international stakeholders come together in hopes of creating win-win solutions to local and global problems. For example, Amsterdam recently launched the AMS Institute , which is made up of several local universities (with support from MIT); multiple local, national, and multinational companies; the city government; and of course new students from the population to cocreate solutions to sustainability challenges in the areas of urban food systems, energy, buildings, and water. The hope is to use the city as a living laboratory to test new concepts, and the ones that can be validated locally will be exported to other cities, hopefully turning to the AMS Institute as not only a mechanism for solving local problems but also for supporting local economic development and new startups.

Of course collaboration is not just about new forms of partnering but also the emergence of the collaborative economy. As my colleagues Duncan McLaren and Julian Agyeman document in their new book, Sharing Cities, the emergence of sharing business models is largely an urban phenomenon. Because of the density in cities, and higher penetration of Internet and smartphones, cities are becoming hotbeds for the collaborative economy. The most obvious examples are those from civic entrepreneurs targeting shared mobility, such as car sharing, ride sharing, and bike sharing. These sharing solutions are very urban in nature and seek to help solve transit problems in cities. But, across the board, most of the emerging business models ranging from food sharing to collaborative renewable energy generation and consumption are decidedly urban as well. In my opinion, we are only at the beginning of the development of urban-sharing business models, yet we are already struggling with how to regulate these models and how to encourage sharing consistent with the needs of their citizens instead of faraway investors and founders. I recently cofounded an accelerator for “responsible sharing economy startups” based in Barcelona. We are partnering with the city government to help screen the startups that are aligned with the city’s objectives and also to help the government identify regulatory approaches to ensure the startups stay on track.

Democratization

The idea that technology and the tools for innovation are being democratized is not new. Yet, increasing democratization of entrepreneurship is supporting even further urbanization of entrepreneurship. Today, aspiring entrepreneurs can tap into open-source software, leverage virtual web technologies, access fab labs for testing and creating 3-D-printed objects for free in their own communities, leverage coworking spaces, and participate in regular meetups in their communities to build their knowledge and networks in order to launch new ideas faster and cheaper than ever before. Democratization not only makes the tools of innovation more accessible to more potential entrepreneurs, it is also reducing dependence on venture capital. While virtually every local economic developer I meet with still focuses on how to attract more venture capital (and perhaps “replicate Silicon Valley”), I believe innovation and entrepreneurship is way less dependent on venture capital than it used to be. It is much cheaper to develop, test, and launch new ideas and tap into the crowd (crowdlending, crowdfunding) to validate and scale new projects.

Of course, the three elements of the “urbanpreneur spiral” interact in a way that creates a circle of support for urban entrepreneurial ecosystems. Innovation districts have been supporting the urbanization of entrepreneurial activity by creating shared resources for the growing entrepreneurial masses. Barcelona was a pioneer when it launched the 22@ innovation district in 2000. The city’s entrepreneurial agency, Barcelona Activa has dozens of activities and physical space to support entrepreneurs and accelerators in the city (or those wish to migrate there). Today there are innovation districts in Buenos Aires, Medellin, and Boston, among many other cities. Because Boston’s project has been so successful, the city is exploring ways to decentralize the innovation district concept to have neighborhood innovation districts throughout the city.

The future of entrepreneurship in cities is bright. And in my opinion, all types of entrepreneurs—tech entrepreneurs, civic entrepreneurs, and indie urbanpreneurs—will all help shape the future of sustainability and economic vitality of our cities.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.