It’s just before 11 a.m. on a Tuesday morning in San Francisco. At the offices of live video-streaming app Periscope–located in an alley next door to a combo café/laundromat/arcade–cofounder Kayvon Beykpour and engineer Aaron Wasserman are huddled in a conference room, preparing to do a Periscope about Periscope. More specifically, it will be about the fact that Twitter’s iOS app has the new ability to display live Periscope streams and replays right alongside tweets, photos, and other elements.

Wasserman starts by shutting off cellular connectivity on his phone, noting that his mom has an uncanny knack for calling him when he’s in the midst of a Periscope session. He and Beykpour discuss whether Scotch, Periscope’s chief canine officer and a constant presence in the office, should be part of the broadcast. (Sorry, Scotch, not this time.)

How long should the Periscope run? “Let’s do whatever feels natural,” Beykpour says. Then he reconsiders, musing that it shouldn’t feel too off-the-cuff. “This is Twitter, it’s a lot of people.”

Moments later, he’s pointing his phone at the desks where other staffers are at work, and broadcasting the scene to the people around the world who are tuning in via the Periscope and Twitter apps. “Hello, everyone,” he says. “Welcome to Periscope headquarters here in San Francisco.”

With 320 million active users, Twitter, as Beykpour noted, is a place with a lot of people. It also happens to be Periscope’s owner, having acquired the startup in January 2015, a couple of months before Beykpour and cofounder Joe Bernstein launched their app, which happened to debut a few weeks after a similar one called Meerkat. Periscope had only 10 million users as of the last time it last disclosed that stat back in August, which means that the new integration into Twitter puts it on a far bigger stage than ever before. But live Periscope streams within Twitter are also a huge deal for Twitter–potentially, one of the most compelling ways for the service to broaden its scope far beyond the sharing of information and opinion in 140-character chunks.

“Twitter brings you closer–it’s the pulse of the planet,” says Twitter senior director of corporate development and strategy Jessica Verrilli, the person responsible for bringing the two companies together in the first place. “Periscope feels like a live representation of that.”

The fact that Periscope lets smartphone owners stream live video as easily and reliably as it does helps explain why it’s grown so quickly: Viewers watch the equivalent of 40 years’ worth of broadcasts a day. But it doesn’t capture the full ambition of its creators, who want to give people the ability to see far-off events in a way that’s new. As Beykpour told me shortly after concluding his broadcast about the Twitter integration, “We didn’t start a live video company for the sake of having a live video company. We wanted to build this thing that–perhaps crazily and stupidly–we keep calling a teleportation experience.”

Before Periscope

Depending on how far back you want to go, the story of Periscope may date to when Beykpour, Bernstein, and Wasserman were grade-school buddies and budding technologists in Mill Valley, California. Or maybe it began in 2007, when Beykpour (by then a Stanford student) and Bernstein founded a startup to build apps for schools. They were joined by Wasserman in the effort, and then sold it to education-technology company Blackboard. After working at Blackboard for a time, along with Tyler Hansen–who later became Periscope’s designer–they left the company, did some traveling, and generally took a breather.

But not for long. “We didn’t necessarily know at the end of that break what we wanted to do, but we knew we wanted to do something together,” Beykpour says. “That process of building something from nothing, we had really fond memories of that experience.”

In 2013, Occupy-like civil unrest broke out in Istanbul’s Taksim Square. Beykpour, who was planning a trip to Turkey, wondered what the situation was like at the epicenter of the protests. There were plenty of people there with smartphones. Shouldn’t there be some way to connect folks at the scene with ones who wanted to see it?

Beykpour and Bernstein began noodling with the idea–which at first didn’t involve video and wasn’t called Periscope. “We started building prototypes of apps that I think were important to get us to where we are today, but look nothing like Periscope,” Beykpour recalls. As they were finding their way, they were joined in the effort by Wasserman and Hansen.

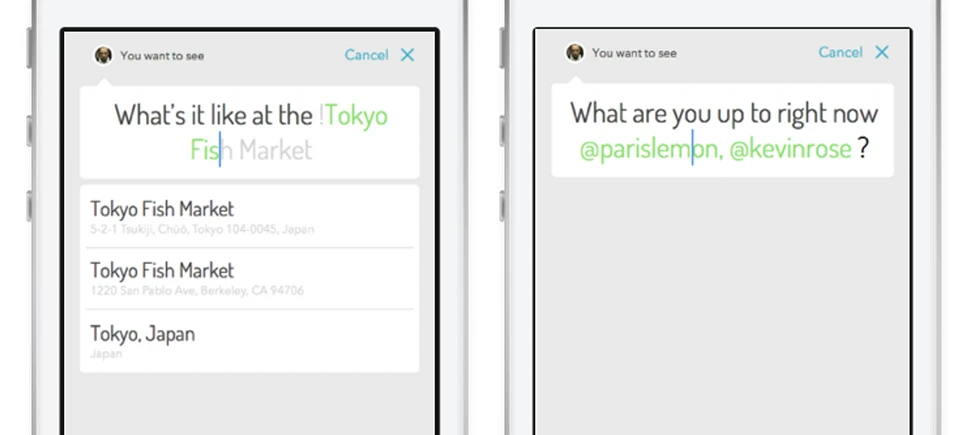

Their most promising idea, which they called Bounty, was a global market for photos. The pitch deck they prepared for investors featured an example: Using Bounty, someone who wondered what it looked like at the Tokyo Fish Market would be able to request an image from a Bounty user who happened to be right there, right then.

Then they had second thoughts. Unless Bounty became enormous, it was far from a given that it would have a user at the Tokyo Fish Market at the precise moment that someone else in the world wanted to be teleported there. And still images could only go so far toward conveying what was going on in another part of the world.

They decided to scrap the notion of users being able to request imagery from specific locations, and shifted their efforts from still photos to live video. With that, the idea that had been Bounty morphed into Periscope.

It was no small decision. Bounty had been a new idea–maybe too new, it turned out. Live video streaming from a smartphone, by contrast, was a long-established category, dating back to the previous decade in the form of apps such as Qik, Justin.tv, Ustream, and Mogulus. None had proven to be a breakout hit. If Periscope succeeded, it would do so on the strength of execution, not novelty.

Working together, Beykpour, Bernstein, Wasserman, and Hansen started to rough out a video-streaming app. Some of the challenges were fundamental and technical in nature. For instance, Periscope would only be compelling if a user could broadcast to large numbers of people with video that was virtually lag-free–and do it over cellular and Wi-Fi connections that can be flaky and sluggish. They managed to make it surprisingly robust.

The design challenge was at least as significant. At first, Periscope videos were square and comments sat neatly below them, for an effect similar to Vine (another video app acquired by Twitter) or Instagram. Then Hansen tried displaying videos in a full-screen, portrait-orientation view, with comments scrolling up right over them and then off into oblivion. The hearts that viewers could bestow upon videos also floated upwards–at first in a straight line which Wasserman compares to the coins in a Super Mario game, and later meandering in more engaging, helium balloon-like patterns.

By August 2014 or thereabouts, the startup had something that was starting to feel special. “Before that release, we’d show the product to our closest friends and our family, and they’d be like, ‘That’s cool, it works, this is live, right?,’ says Beykpour. “But it never really stuck. After that release, people would experience a Periscope and they would just literally say, ‘holy shit.'”

Creating Periscope turned out to be as much about editing features out of the app–sometimes only after building them–as it was about the functionality it did have. At first, its designers were concerned that it would suffer from a dearth of content. “We used to speculate as to at what point after we launched would we cross the milestone where we could say there was at least one broadcast going for a 24-hour period,” Beykpour says. So they built in a feature that would let users schedule broadcast in advance for particular days and times.

And then they scrapped that tool, after concluding that users weren’t going to methodically peruse lists of scheduled video on a smartphone screen. Instead, Beykpour says, “you get a push notification. If the subject is interesting, you probably will open it. If it’s not, you won’t.”

Enter Twitter

With Periscope shaping up into something intriguing, Beykpour gave his friend Jessica Verrilli a demo over coffee. After meeting Beykpour at Stanford, she’d gone on to join Twitter in 2009, when it was still a tiny startup with huge potential.

Beykpour had first shown Verrilli his startup’s project when it was still a photo-sharing app called Bounty. Periscope was something radically different, and from the moment she saw it, the possibility of bringing it together with Twitter sent her mind racing.

“It was immersive, live, emotionally resonant,” She remembers. “It showed you what was happening in a way that felt Twitter-y. It felt like these two products fit together.”

Selling Periscope so early in its history would mean giving up at least some measure of control over its destiny, and would eliminate any scenario of it becoming a unicorn unto itself. In fact, Beykpour and Bernstein thought they weren’t interested. “We were like, ‘A) wow, we’re honored, and B) thanks, but no thanks,” Beykpour recalls.

But after talking to Twitter’s then-CEO Dick Costolo and its chairman/cofounder Jack Dorsey, Periscope’s founders concluded that their startup could keep on acting like a startup under Twitter ownership, while also enjoying some of the benefits of a close relationship with one of the web’s giants. As Beykpour puts it, Twitter “just wanted to be the wind behind our sails.”

The deal was done, reportedly for less than $100 million. Not long thereafter, rival Meerkat launched, became a SXSW wunderkind–and then found its access to Twitter’s social graph curtailed shortly before Periscope went live.

Twitter agreed to let Periscope operate out of its own office, a 15-minute walk away from Twitter headquarters–close enough for frequent visits, but still with a degree of separation. At acquisition, it had seven employees; that number now stands at about 30, and includes a couple of former Twitter engineers whose transfer over is helpful for projects such as integrating Periscope into Twitter’s apps.

Periscope is hiring, but has no plans to grow ginormous any time soon, in part because it can borrow resources from Twitter as appropriate. Twitter’s legal affairs group, for instance, is responsible for mundane-but-essential matters such as crafting Periscope’s terms of service and privacy policy. Being part of Twitter also helps boost Periscope’s prominence as a pop-culture phenomenon: When someone at Periscope wants to be introduced to someone such as Jimmy Fallon or Italian comedian/singer Rosario Fiorello, there’s generally a person at Twitter who can make the connection.

Just as important, Periscope is leveraging the technical expertise that Twitter has accrued after a decade of tackling challenges with many parallels to what Beykpour, Bernstein, and company are building. Beykpour says it’s happening in an unstructured, informal way: “We’ve had fundamental improvements to our product that have come about as a result of a happy hour where some data scientist at Twitter will be like, ‘Hey, I was thinking about how you guys rank your feeds, and it seems to me that there was no rhyme or reason on how you do that right now. I put together this algorithm that you might want to look at.’”

“Product-wise, we make all the decisions here,” he stresses. “Twitter has been incredibly respectful of the fact that we run our show, and we launch what we launch and we launch it on the timeline that we want. And we use the language that we want and if we want to swear on a broadcast or in a tweet we can do that. It’s just our thing.”

In multiple ways, Periscope feels like it’s at a point roughly comparable to where Twitter was circa early 2009, when it had about the same number of employees that Periscope does today, and a user base in the same ballpark. Like early-2009 Twitter, it’s not yet a place where celebs and brands feel obligated to have a presence, but is already one where some are having fun, experimenting, and otherwise exploring what’s possible. David Blaine uses Periscope to livestream magic tricks; BMW chose it to announce a new car.

“We didn’t want to build a celebrity broadcasting app for the sake of having that, but we knew that if we did a good job, people with large audiences would be compelled to use the medium,” says Beykpour. “Some of our favorite actors or musicians or comedians will pop onto Periscope, and we’ll be like, ‘Wow, it’s crazy that Jamie Foxx even knows what Periscope is, let alone that he’s using it all the time.'”

At its best, Periscope has moments of interactivity that are hard to imagine happening on other services. “When musician John Mayer gets on Periscope, he doesn’t always play music, but when he does, he sometimes takes requests from commenters. “Some of them are for John Mayer songs,” notes Wasserman. “But I was watching this one time and someone requested: ‘Can you play the Star Wars cantina song?’ He literally live-figured-out the Star Wars cantina song and blended that with whatever else he was playing before that. Talk about breaking the fourth wall. Whoever suggested that, I’m sure they’d be hard-pressed to forget that experience.”

Which is not to say that Periscope–a company kickstarted by Beykpour’s interest in the Istanbul protests–aspires only to be a celeb-fest. “The [Syrian] refugee crisis was movingly and extensively covered on Periscope,” Beykpour says. “It’s very episodic in the sense that there are a couple of outlets and individual journalists who cover the refugee crisis and every other day or every week or definitely every month, you hear from the same folks covering that story. It’s not the most lighthearted content to watch but it’s exactly the type of thing we want people to be able to share and learn from on our platform.”

More To Come

Being part of Twitter gives the Periscope team the opportunity to continue to focus on building out the experience without getting immediately hung up on making money. Beykpour says he has some ideas on how to turn a profit–which presumably could resemble such Twitter elements as sponsored tweets–but “we’re deliberately not focusing on that right now, because we feel like we’ve got a laundry list of things we want to do first.”

“People are using this product and that actually affords us the ability to make some really big leaps that we either never dreamed about, or could dream about a year ago, but there was just no point in even bothering because we didn’t have anything,” he says. “2016 will be a busy year for us.” Adds Twitter’s Verrilli, “I think what you’re seeing is just the very beginning of what we can do together.”

Periscope is working on new features, and it won’t be long until some of them are live. And while Beykpour is as reluctant to pre-announce them as you’d expect, he does say that that there’s plenty of opportunity to provide more tools to the relatively small percentage of Periscope users who do most of the broadcasting.

“If you think about the leverage that you have at your disposal as a broadcaster right now, you have your voice and you have your camera,” he says. “Those are the two things that you can control. We think that there are actually other things that we can provide you as levers to create more creatively. If people aren’t creating there’s nothing to watch.”

Periscope is also developing more ways to find stuff to watch, beyond current features such as the ability to follow other users and pull up a map showing where live broadcasts are going on right at that moment. “The more broadcasters there are, the more there’s a signal-to-noise problem,” explains Beykpour. And it’s at least mulling over the possibility of allowing videos to live on the site indefinitely in replay form. (Currently, they vanish after 24 hours even if a broadcaster chooses to make them replayable.)

For all the energy Periscope is pouring into self-improvement, it’s the broadcasts that define the experience, And if the service feels substantially different in a year or two, it might be because community members have discovered new things they can do with it–another factor reminiscent of Twitter in its early days.

“Every day, we see ways in which people use the product that we never would have imagined,” Beykpour marvels. “That’s been one of the coolest things to experience. It’s like a sociological experience working here every day.”

Related: What Is The Future of Video?

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.