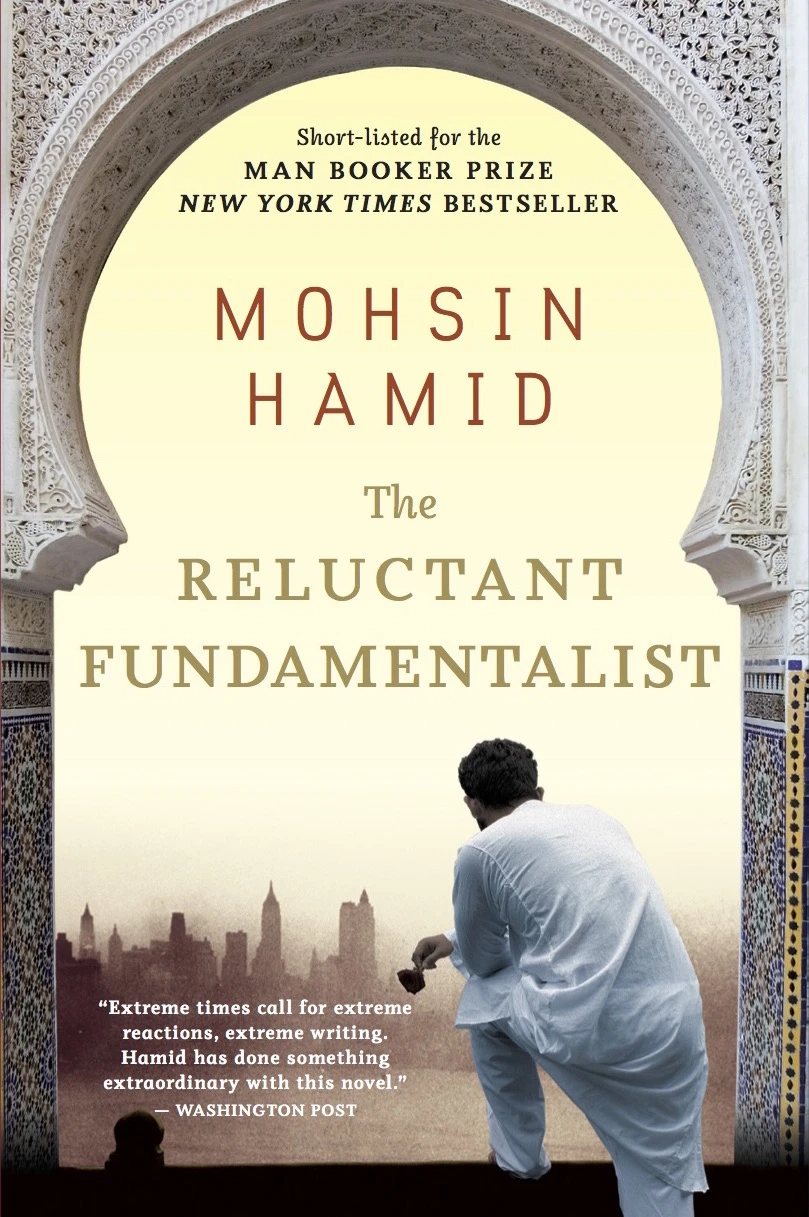

True story: In 2007, the Pakistani writer Mohsin Hamid catapulted into the literary spotlight with his second book, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, an examination of the harsh realities of America’s fractured post-9/11 relationship with Muslims. The book sold over a million copies worldwide, was turned into a Mira Nair-directed feature film, and was short-listed for the prestigious Man Booker Prize. The Guardian called it one of the books that defined the decade.

Given that he’s one of those rare, respected literary intelligentsia who can actually make a comfortable living from writing novels alone, I was surprised to learn that Hamid has recently started a new chapter: He’s now working for the half-century-old creative consultancy Wolff Olins as the company’s first chief storytelling officer.

The CSO is a thoroughly modern title, the product of a growing interest in corporate storytelling, a pursuit that has lured other established writers and journalists into the world of corporate hackery. LinkedIn lists two dozen executives who have held CSO positions, a trend that may have begun at Nike in the ’90s. (“Our stories are not about extraordinary business plans or financial manipulations. . . . They’re about people getting things done,” Nike’s then-chief storytelling officer Nelson Farris told Fast Company in 1999.)

Hamid’s job isn’t to shill for Wolff Olins or tell its own story, but to help its clients learn how to tell theirs–or find out what their story is to begin with.

“Stories are fundamental to how we think about the world,” Hamid tells me by phone from his home in Lahore, Pakistan, where he lives with his family when he’s not traveling between London or the States for work or research (he’s working on his next novel now). “Nelson Mandela told a story about what post-apartheid Africa could look like. That story was persuasive enough to promote change, and it became reality. JFK told a story about putting man on the Moon, and it inspired people and came to pass. These types of huge events were built on stories.”

Hamid’s own story is winding and global. Born in Pakistan in 1971, he spent his childhood in America as his father, a university professor, worked on a PhD program in economics at Stanford University. Hamid returned to Pakistan with his family during his teenage years before coming back to America in the early ’90s to earn his undergraduate degree from Princeton, during which time he began working on his first novel, Moth Smoke. In 2000, after he earned a law degree from Harvard, the book was published to wide acclaim. Next came The Reluctant Fundamentalist and his 2013 novel, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, which Michiko Kakutani wrote “reaffirms his place as one of his generation’s most inventive and gifted writers.” That year, his writings on politics and culture earned him a spot on Foreign Policy‘s Leading Global Thinkers of 2013 list.

Last year, Wolff Olins–which in 2001 became a subsidiary of the marketing giant Omnicom Group–contacted Hamid to explore how he could contribute to its work; the more he thought about it, the more he recognized, he says, that “storytelling isn’t only for novelists, but CEOs and leaders as well.”

That’s the prime audience of Wolff Olins, which has helped craft messages for everyone from the Beatles’ Apple Records to the London 2012 Olympics. “They really want to be the creative partner to CEOs, and Wolff Olins discovered that many CEOs feel they don’t have the knowledge necessary to tell good stories, so they approached me about that–about what a novelist could bring to the table,” he says. “I’ve always been interested in form as a writer and how stories get built, the different techniques that can be used. I was intrigued by the possibility of the novelist’s skill set being used in business.”

The Power Of The Internal Story

Most companies, of course, are no strangers to telling stories. They do so with every press release they put out and every advertisement they display, carefully crafting messages to persuade people into buying their products and services and supporting their causes. But after it surveyed almost four dozen global CEOs, Wolff Olins discovered that even though many company leaders feel comfortable crafting external, customer-facing narratives, they often feel less sure of how to articulate an internal story for the company.

More than just a feel-good theme, Hamid says a unifying narrative that all employees can grasp can help them work more creatively and independently–necessities in today’s company structures, which often rely on a distributed leadership approach, rather than the top-down supervision of yesterday.

“How do you empower people inside a company to do their own thing, to try to innovate, to not be a completely top-down organization, to be an organization that is creative and inventive?” he says. “You can’t do that as a CEO by telling everybody, ‘Here is your set of marching orders.’ It’s just too much. You don’t have the capacity to do that.”

Instead, Hamid underscores the importance of a clear narrative, one that allows others to appreciate the overall vision of where the company is headed and allows them to use their own creativity and approach to help it get there.

This is particularly important when dealing with younger workforces, he says: “You have young people who are used to being managed in a different way or not managed at all. To have people like that, to have creative thinkers in your company who are the people who are going to innovate and come up with new ways of doing things–to excite and attract and motivate and direct those people–you need something very different in your toolkit, which is really more about storytelling than it is about simply commanding.”

Besides being good for employee morale and creativity, the process of crafting an internal story often has ancillary benefits. “The exercise of storytelling is a creative way to think about strategy,” says Hamid. Often, leaders who are trying to create an internal story find that their perfect ending they want to convey to their workforce isn’t actually achievable under current plans. That allows them to start thinking creatively about a strategy that will help them achieve that ideal ending they want to tell.

“That whole process is like a drafting process,” Hamid says. “You might be called in to help someone craft a story about their organization and then you wind up entering into a strategic conversation. That may not be what you were initially asked to do, but very often that is what winds up happening. Creating the story is about reshaping a strategy.”

When It’s Time For Telling Stories

Hamid says there are three moments in a company’s life cycle when most leaders become aware of the importance of internal storytelling. The first is at birth. “If you’re a new company, or if you’re a company entering entirely new territory, you have to explain what you are internally, because nobody knows,” he says. “So storytelling is fundamental to what startups do, and the companies that come out of the startup world—the Apples and Googles of the world—still very much partake of that startup ethos, so they take storytelling very seriously.”

The second opportunity for storytelling comes when new leaders arrive, or when a company is acquired. “After that event, storytelling is very important to articulate what the new direction is,” says Hamid. A third occasion for storytelling is when a company seems to be having difficulty growing. “Companies that have a legacy but can’t see where the future growth is coming from very often have a heightened awareness of story, because they need to articulate the way out of what seems to be decline.”

For those who currently find themselves at any of those three points, Hamid offers some tips for crafting your company’s internal story, to motivate your employees and maybe discover new strategies along the way.

1. Be True

“To have a powerful story, it has to be grounded in reality,” he says. “It has to be grounded in the truth of what a company is, who you are as CEO, and what is really going on.”

But Hamid notes that many times the first story a company’s leader crafts is a mixture of fact and fiction. Instead of cutting out the fiction, Hamid says, embrace it as a tool for change. “If you find that the story that you want to tell isn’t true right now, well, that gives you a strategy. You have to do what it takes to make that come true so that you can tell that story in the future, because that’s a future story of your company. Use the truth as your touchstone; any gap between the desired story and the truth is a way of picking out what you need to do in the future.”

2. It’s About “You,” Not You

Hamid’s second tip for storytelling is to think about your audience and frame the story as it relates to them.

“Very often when companies speak and people in companies speak, they speak in either the first person or the third person. They speak, ‘I am doing this’ or ‘we stand for this.’ Or they speak in the third person—’the customer needs this; the customer needs that.’ What’s quite neglected is the second person, ‘you,’ and I think the ‘you’ in the second-person form is very powerful.”

Hamid points out that religious texts have used this second-person address to spectacular success over the centuries. “You see the second person very often used in religious texts, and that’s not a coincidence. Religious texts speak to ‘you’ because doing so conveys the notion that the person being spoken to really matters; it really shapes what a story does and how it functions. So I think when you are speaking to the employees of a company, that notion of second-person ‘you’—what do ‘you’ feel? what do ‘you’ want?— is very helpful.”

Hamid also notes that though most religious texts set out rules, those rules are usually communicated through storytelling. “Religions can just say, okay, well, here are the rules: Don’t drink alcohol. Don’t eat pork. Fast 30 days a year. But they don’t tend to communicate themselves in that form. Religions tend to communicate through storytelling because stories have power.”

3. Don’t Be Afraid Of Emotion

When was the last time you were in a business meeting and someone asked you to share your feelings? Probably never. But that’s exactly what you should be thinking of sharing when you craft your internal story, Hamid argues. “So much of business and what people are taught about business is rational thinking, logic, Excel spreadsheets, models–a particular business school way of speaking. It’s about logic and rationality and reason. And that’s all very important, but it’s not enough.”

“It is equally important to have emotion. People have to feel something, and you have to feel something–you the storyteller.”

When using your story to convey the goals of the company, for example, don’t just talk about selling X number of widgets; talk about how you see those widgets affecting the individual lives of the people who use them.

4. Keep It Simple

Resist the Joycean urge. “There is a tendency, I think, to overcomplicate, to think that stories have to be very complicated,” Hamid says, “but there aren’t really that many different types of story in the world. There are only a few: human against human, human against nature, thwarted love, et cetera, et cetera. Actually cutting through to the essence of what the story is while at the same time tapping into its truth and emotional essence is the way to go.”

5. Hire A Novelist

If you’re more spreadsheet and metrics than storyteller, maybe it’s time to hire one. (They’re plentiful and often looking for extra income, believe me.)

“The storytelling impulse is something that exists in many of us, most of us, maybe all of us,” says Hamid. “But in some, it exists very, very strongly; so strongly they choose to go into professions like being a novelist, being a storyteller.”

But Hamid believes that it’s time for everyone, card-carrying storyteller or not, to realize that the skill of storytelling is something that can be applied by many people in many different contexts.

Telling stories “can be applied to vaccination programs. It can be applied to politics. It can be applied to religion and it can be applied to business.”

For proof, Hamid points to the closing gap between artists and businesspeople. “There’s almost a kind of iron curtain that had separated those people who pursue the arts and go into writing from those who pursue management or business or nonprofit, and I think that is an artificial distinction. There’s no reason why different types of people can’t bring together different types of skills to build better things together.”

It’s an argument that he can back up with his own story.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.