“My life was full of serendipitous events, real-life meetings, Frisbee, bike rides, and Greek literature,” Verge writer Paul Miller explained after his year away from the Internet. After Baratunde Thurston’s month unplugged, he gushed in Fast Company that, “There were movies, there were food trucks, there were friends, there was mulled wine. There was brief consideration of a mulled-wine food truck. But above all, there was an expansion of sensations and ideas.” And David Roberts, a prolific political blogger known as Dr. Grist, put the initial effects of his offline hiatus like this: “I discovered that calm was like a drug. It felt so good, so decadent, just to sit in the early afternoon with my feet propped on the windowsill, watching wind brush the trees in the front yard.”

I read these reports from the offline world with the drooling envy of an armchair traveler. I want Frisbee! I want bike rides! I want window gazing and food carts and mulled wine! I want to discover that calm that’s like a drug.

But here’s the thing: I have a job and a life that make it impossible for me to go offline for any extended amount of time.

I will admit that my daily work regimen–which involves two computer monitors, four simultaneous columns of chatter on TweetDeck, a Slack chatroom, two email accounts, and dozens of simultaneous tabs open in two different browsers–isn’t doing much for my peace of mind. And research seems to be pointing in a pretty clear direction. One study found screen time somehow interferes with children’s ability to read emotion in others. Another, a correlation between multitasking and less gray matter in the area of the brain associated with cognitive and emotional functioning. Heavy multitasking has been correlated with an inability to focus, stress, depression, and anxiety. Studies even suggest multitaskers are, ironically, worse at multitasking than their single-tasking counterparts.

Unplugging, though, can’t be the only answer. What if the solution to my tech problems was actually more tech? What if we don’t need to hatch elaborate plans to lead analog lives?

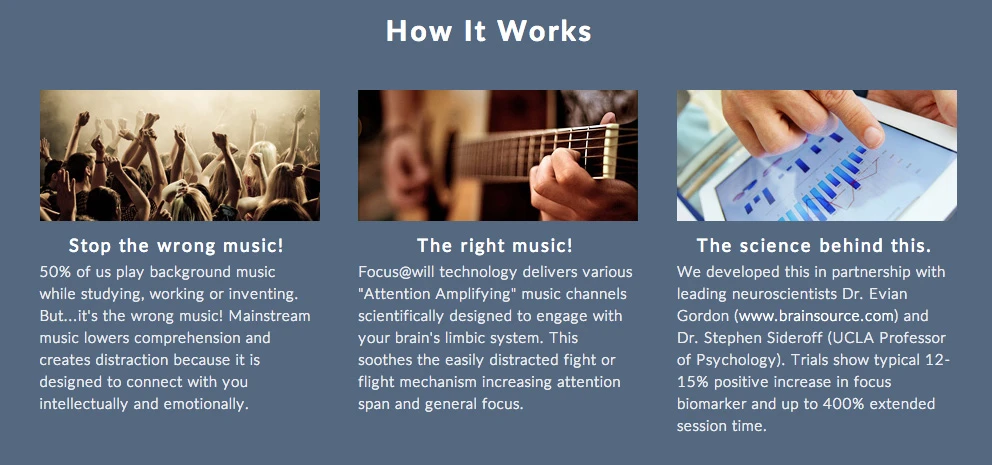

This fall, those questions arrived on my desktop with the familiar dopamine rush of a new email notification ping. “Eliminate distractions!” the subject read, adding parenthetically, “But not this email, it’s important.” It was a PR pitch for “a neuroscience-based productivity tool that streams personalized music tracks and sounds to subtly engage your brain’s ‘fight or flight’ response, allowing you better focus without your internal distractions.” Maybe the claim was dubious, but it also seemed, oddly, worth a shot.

Like the digital rehab patients before me, I decided to embark on an immersive project: the inverse of unplugging. For a month, I would try a myriad of new products–sensors, brain-wave readers, breathing monitors, meditation apps, online happiness courses, and just about every focus tool I could get my hands on–in pursuit of a digitally enhanced zen.

An Old Problem

Anxiety about technology has been around for as long as technology itself. When Henry Thoreau pioneered the unplug memoir more than 150 years ago–longing for the “very simplicity and nakedness of man’s life in the primitive ages,” arguing that “men have become the tools of their tools”–the first commercial electronic telegram had just been tapped out in Morse code. Socrates famously argued that the most promising new technology of his day–the written word–would “create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories.”

This is way, way before Google.

So maybe staying calm in the face of innovation isn’t just this generation’s problem. Neema Moraveji, who started Stanford’s Calming Technology Lab, has spent most of his academic career studying ways technology might provide a solution. “One of the things I think we will someday say,” he says, “is, ‘when these devices came out, everyone was consumed and distracted and couldn’t get a hold of their own minds.’ Then they figured out, ‘let’s put state of mind into the device.’”

His idea, which he took a leave of absence from Stanford to co-create, is called Spire. It’s a $119 pebble-sized device that clips to your belt and tracks your breath by sensing when your abdominal muscles engage. When your breath indicates you’re tense, which research suggests it will, Spire offers exercises–like taking deep breaths–that other research suggests could help put you back into a state of calm or focus. “You can do it any time,” Moraveji says, “you can do it while you’re doing other things. But you can increase your awareness.”

Adding another charging cord to my desk (In Spire’s case, it’s a pad) isn’t ideal, and I already have a small collection of wearable devices that I abandoned days or weeks after purchase. But I snap a pre-production version of Spire to my belt anyway.

So begins my month-long calming technology binge.

Plugging Way In

A quick search for “mindfulness app” surfaces a video from Arianna Huffington, the most visible advocate for a well-managed digital work life, demonstrating a free app she launched in 2012 called GPS for the Soul, which, she explains, “interrupts the downward stress spiral, and puts things in perspective.”

I add it to my phone’s home screen.

Focus@Will, the neuroscience-based music service with the well-timed PR emails, in practice looks like a simple music player with a timer function. It’s free for 30 days, after which the price jumps to $4.99 per month.

It only takes a couple of clicks to sign up.

The company that makes Lumo Lift, a small $100 gadget that monitors your posture, says its mission is to “help people become more mindful, and empower them to make the small but powerful changes that improve their lives.” In Lumo Lift’s case, that involves a coaching mode that buzzes you when you slouch. It’s like my mother, in an app.

I snap it to my shirt.

There’s something admirable about the simple, straightforward approach of a Mac app called Freedom. For $10, it blocks your access to the Internet–which, again, would be great if the Internet weren’t a necessary part of my job. Instead, I download Time Out, a Mac app that promises to break bad computer habits with reminders to take micro-breaks. I also install RescueTime, a plug-in that tracks the time you spend on certain websites and applications. Diagnosing the problem, I reason, seems like the first step toward solving it.

For good measure, I throw in a couple more simple apps. DoOneThing “is intended to bring your focus back to what is most important for the day, to make your primary goal present in your computer screen and life.” All it does is ask what you want to focus on and posts it at the top of your screen, next to the clock. Calm Down’s creators write that you can use their app “to help focus your breathing and calm yourself.” It’s a yin yang symbol that pops up next to DoOneThing. When I press it, my computer screen flashes between blue and gray in the rhythm of a slow breath.

My open-office colleagues are going to think I’m crazy.

Then again, maybe I already am. That night, I discover myself standing above my kitchen table, where I had been eating dinner, with my phone open to Instagram and not the slightest memory of why I had gotten up. Oh yeah, I finally remember just as I sit back down at the table. I need a butter knife.

Getting Buzzed

GPS for the Soul, it turns out, is built around the type of slideshows that grandmothers stopped forwarding in 2003. I open “A Meditation For Optimism” and force myself to sit through a parade of sunsets and mountainscapes overlaid with classical music and positive messages like “I will forgive others,” “I will prioritize my well-being,” and “Good things are going to happen.” Gail McMeekin, the author of another “guide” called “The Power of Positivity,” has slightly better taste in clip art, but I find her instructions–“Find your life purpose and live it,” “Seek out peek experiences”–a bit too vague to implement effectively. In “Meditation For A Clear Mind,” by leadership coach Scott Coady, I am encouraged to “Embrace the mystery of the wonder of creation” and “Love the mystery that is the journey of your life.”

I am hating the mystery that is the journey of this app. Initially I don’t fare much better with the others, either.

Lumo Lift’s “coaching mode” buzzes me every time I slouch, which is almost constantly. The version of Spire I have is an early prototype, and one of its bugs makes the device buzz so often that it congratulates me nine times for being active during my 30-minute morning commute (this is particularly cumbersome on days when I wear a dress and cannot clip Spire to my belt, when Spire’s instructions suggest clipping it to my bra instead). Time Out interrupts me for my “micro-break” every 10 minutes by fading my screen to gray and replacing it with a neon green clock graphic and an outline of a meditating yogi, which means I clench my teeth with annoyance about every 10 minutes.

In addition to all this buzzing and interrupting, I seem to have developed a new “calming and focus app” multitask pattern. I click on RescueTime to see how much time I’ve been wasting (three hours on Gmail alone). I click to my Focus@Will tab to see what song is playing (“Concerto Grosso IV”). I open Lumo Lift’s app to see my posture status (“slouchy,” generally). I download a new app called Checky that keeps tabs on how often I check my phone, and before long, I find myself checking my phone to see how many times I’ve checked my phone.

I’m pretty sure that I am not achieving the advertised “balanced mind” or “mindfulness” through this cacophony of technology, though it occurs to me that I wouldn’t know it if I did. My whole objective is about as specific as Gail McMeekin’s life advice. No wonder I’ve only succeeded in annoying myself.

The Human Touch

Maybe it’s time to find a guru. Or at least someone who knows what a guru actually is. Michael Craft, the business and program development strategist at the Omega institute, has been practicing tai chi chuan, qigong, and mindfulness meditation for more than 30 years. Surely he can help explain what I’m supposed to be aiming for.

“Are you feeling more patient?” he asks me when I call him. “If someone is just nattering on, are you more able to be present with that, and are you able to be more focused on a previously boring task?”

Well, I haven’t checked Twitter yet during this phone call. That’s something, right?

Craft explains that what I am most likely to notice in becoming “more mindful” are improvements in self-regulation, the ability to recognize and change states of mind (say, realize I’m becoming stressed and calm myself down), as well as executive function, the ability to observe and make decisions from that relaxed place.

Nightline co-anchor Dan Harris mentions a similar feeling in his book about meditation, 10% Happier, which is my latest armchair-travel-style read. Here’s how he explains it: “Mindfulness is the ability to recognize what is happening in your mind right now–anger, jealousy, sadness, the pain of a stubbed toe, whatever–without getting carried away by it.”

But what about the calm drugs that the other unpluggers are talking about?

Moraveji breaks the news to me gently: “Saying we should always be blissed is like saying we should all be as skinny as possible,” he says. “That’s not healthy either.” According to him, awareness is more like learning a new language. “It’s like all the sudden there’s a new dimension in your life that is not vague, but is very real and something you can do something about,” he says, “and you don’t just suppress it and ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist, but rather it’s in parallel to your daily, worldly life.”

It may not be euphoria, but it does sound better than what I’ve been doing. Whatever “it” is. For all I know, Craft (who has also authored a book about UFOs), Harris (a self-avowed cynic), and Moraveji (an academic) could be talking about completely different sensations.

But as different as their perspectives may be, all three manage to agree on one way to achieve this focused, mindful sense they describe, and it doesn’t involve corny slideshows. Just paying attention to your breath.

You’d be surprised how many technologies you can employ to help you do something so excruciatingly simple.

Finding A Muse

“Blink,” Ariel Garten, the CEO of the company that makes a brainwave-sensing headband called Muse, instructs me. She’s already helped me position the black plastic gizmo around my forehead, and we’re watching the bouncing color-coded waves that have just appeared on her tablet. They jump when I blink. “That’s you,” she says. “You’re alive.”

Research has linked mindfulness-based meditation with improvements in depression and anxiety, focus, and stress. A Harvard neuroscientist found people who practiced meditation had a thicker layer of tissue in the area of the brain thought to integrate emotional and cognitive processes. But despite science that has convinced institutions from the military to General Mills to give meditation a try, I’ve never been able to attend a class without wondering when someone will ask me to give up my worldly possessions and commit my first-born child to the cause. Blame my rural Midwestern upbringing or my immersion in the New York-media cynicism machine, but the chanting, the calls for peace, and the pseudo-religion present in most meditation teaching venues make me uncomfortable.

Muse, however, has been stripped so thoroughly of any hint of mysticism that its parent company refuses to even call it a meditation tool, preferring instead the term “brain fitness.” Just like you do reps at the gym to build your body muscle, it treats practicing focus like doing mental reps for your brain muscle. The gadget’s accompanying app, Calm, asks you to close your eyes and count your breaths, notice when your mind wanders to something else, and bring it back to that task (essentially, basic meditation instructions). Well-behaved brainwaves trigger soothing nature noises. Active brainwaves result in loud wind noises. Achieving what the app deems “calm” is like scoring a point, which is indicated by the sound of a tweeting bird. All of this can be reviewed after the session is over, like checking a Fitbit app.

I blame my initial poor performance on the awkwardness of Garten being in the room.

During my first independent session, I realize that I’m kidding myself. I get a text message two minutes in and pause to check it, and even without Garten watching, I can’t stop thinking about work. What is for lunch? Is this headband is on right?

It takes me three days before I hear my first bird, which makes feel so oddly accomplished that I email Muse’s PR representative (the only person I know who will understand what I’m talking about) to brag.

My real breakthrough, however, comes when I bring Muse home for the weekend, and it is not necessarily driven by peace and love.

Because my husband directs digital media for a yoga festival, he spends all summer attending events with meditation workshops. He’s not only eager to try Muse out, but a little bit smug as he takes a cross-legged seat on a yoga block in our living room.

Five minutes later, when he removes Muse and we look at the data, the tables turn. During his meditation, he didn’t land a single bird. He’s only spent 25% of his time in a “calm state,” which is less than my worst session so far.

Suddenly I feel like I’m back in high school, waiting on a swim block to start a race I know I can win.

And indeed, when I take my turn with Muse, I knock this one out of the park: 16 birds (15 more than my record and eight more than I will ever achieve again) and 78% calm. “How do you feel?” the app asks me as it congratulates me on my best session ever, “Pretty amazing, right?”

It has no idea.

Getting Rhythm

It’s not until about two weeks in that I start to develop a routine that feels like an improvement over my original attention-ping-pong work strategy.

I retire Spire until its final product is ready (which, for the record, when it does arrive, does not overbuzz and works as intended), restrict my analytics checkups to weekly newsletters, delete Time Out forever, relegate Lumo Lift coaching to one hour a day, and recognize GPS for the Soul as an app designed mostly to promote the Huffington Post.

After locking myself in my office building’s cold, windowless call room to use Muse each morning, I come to my computer and set an intention using DoOneThing (I use words like “intention” now). The little piece of hovering text is surprisingly helpful at keeping me on task. It feels like a little nudge of accountability when I lose myself in Twitter. “Hey,” it says,” you were supposed to be doing this thing, remember?”

To my surprise, I’m also still using Focus@will, and I love it. Its founder, a musician named Will Henshall, says it works by occupying the part of my brain that unconsciously scans my environment for danger. He does have neuroscientists advising his company, but his more simple explanation still seems more plausible. “Anything about music that people like,” he says, “is going to distract you.” So Focus@Will makes electronic music with no drops, acoustic music with no strong melodies or chorus, and classical music without cellos, saxophones, or bassoons (they sound too much like human voices, Henshall says). I may not be able to find an independent, published study on the topic, but it works for me.

I’ve also replaced GPS for the Soul with Happify, an app that, as its name implies, claims it can train you to be happier. Its exercises include a game in which you must pop hot air balloons overlaid with positive terms like “inspire” and avoid negative terms like “whine,” polls like “how would you get messy?” dancing, and meditating. At the least, each task comes with a research-backed explanation about why it should be effective in improving your outlook on life. I consider it a tremendous improvement over the slideshows and try to complete one or two while eating lunch. Sure, it’s multitasking, but it’s mindful multitasking, I tell myself.

Then I spend 10 more minutes in the call room completing meditation exercises with an app called Headspace, which was created by a former Tibetan monk (and degreed circus arts performer!) named Andy Puddicombe. Unlike Muse’s Calm, this app doesn’t attempt to quantify anything. For the most part, it’s just Puddicombe delivering meditation instructions in a rich, pleasantly accented voice.

Per his instructions, I notice the sounds around me. I mentally scan my body for where I feel good or tense or uncomfortable. I bring my attention to my breath. I think about the thoughts that distract me from this as cars passing by me on the street that I don’t really need to mess with. And I spend a few moments considering the effect of doing all this.

Then I plug back in at my desk and launch my hodgepodge mindful working environment again, sometimes throwing in a Lumo “coaching session” to keep my shoulders back for optimal breathing (and, I convince myself, less likelihood of death by chair).

This routine doesn’t take much time, probably about 30 minutes out of my day, but it makes brain feel calmer. I’m landing birds more regularly in Muse. According to RescueTime, my “productive time” has increased steadily just about every week, from 59% to 63% of the time I spend on my computer. While I checked my phone more than 70 times on the first day after I installed Checky, I only checked it 45 times on the last day of September.

What’s happening is not magic, but it is improvement. Now I push the new yin yang on my toolbar, the one that launches your screen into a breathing exercise, when I start to feel like there is no way to keep up with my pings, stay up on the news, and still finish this article. It’s the same flustered feeling I have always experienced. The progress, from what I understand, is recognizing when to push the button.

Graduation

But I still have a week to go and I cannot get the left side of my forehead to light up in Muse’s Calm app. I’ve been sitting in the call room for 15 minutes with the black plastic headband pressed against my forehead, but no matter how many times I adjust the left band, and then the right band, and then the left band, I cannot get the sensor above one eyebrow to connect in a way that will make brainwaves appear on the app. I feel myself growing quite the opposite of calm–an awareness I can only attribute to my weeks of mindfulness apps.

Finally I give up. I set the headband on the table in front of me and navigate to Headspace.

It’s the last time I use Muse. I worry this might signal that I’m becoming less, not more, patient, but the device did get me started. It helped me answer the nagging question of “Am I doing this right?” and, by fueling my need to quantify and compete, it prevented me from giving up on meditation before I could feel why it might be useful.

By using these definitively non-mindful desires to help myself meditate, was I somehow cheating? I ask Craft for his professional opinion. He is kind. “This is no different than sitting down with a teacher every day,” he says, “This is just replacing that teacher with a device that can do it for you and maybe make it easier to do because you can take it with you wherever you go. It is exactly as valuable as beginning meditation.” After all, he says, meditation has always incorporated some “technology,” beginning with going into a cave to shut off distractions. Is my quantified meditation that much different than the Buddhist monks who measured the length of their sessions by the number of incense sticks they burned?

Yes, it is, says Levi Felix, the founder of a company called Digital Detox that hosts summer camps, corporate retreats, and parties where attendees must check their devices at the door. He thinks Muse is more like those superfluous apps that tell you when you are thirsty and need to drink water (there are more than 50 of them) than a conveniently quiet dark cave. “We’re fucking humans,” he laughs when I run my question by him, “We’re alive because we have known when to drink water for the last thousands of years of our development. It’s a fine line as a society to use devices and develop them and to become reliant on them.” In other words, we should be able to feel for ourselves when need to take a few breaths.

Fair point.

What I do know about Muse, however, is that I don’t need it anymore.

Now I have no trouble sitting through Headspace’s 10-minute and (because I’ve graduated to level two) 15-minute mediation sessions. In fact, I don’t like to miss them. Muse has worked like training wheels to get me to un-quantified meditation. And I guess even Headspace, far from a human relationship with a teacher, is also a form of training wheels.

But at least I’m training.

Pulling The Plug

On the last weekend of my experiment, I actually do unplug. My husband and I rent a renovated old schoolhouse next to a creek in Woodstock, New York, and though the rustic, barn-like building is technically Wi-Fi equipped, neither of us brings our computers. We spend a couple of days eating at vegan restaurants, downing butter-packed cupcakes, and hiking in the Catskills.

The day after a particularly grueling hike, we wander into a yoga studio seeking relief from our cramped quads. I soon realize, after being corrected kindly by the woman who hands us waivers, that this is the kind of place where one does not “do” yoga but “discovers yoga within themselves.” Usually in this situation, I locate the nearest exit. But this time, I stay for the whole chanting, peace-invoking shebang.

Even Felix doesn’t advise disconnecting completely forever. He sees detoxing as a tool for diagnosis, the way doctors might see a restrictive diet–a way to understand what is making you sick and what is safe to reintroduce. “Someone might unplug for four days and be like, ‘Oh, I don’t have a problem,’” he says. “Someone might unplug for four days and be like, ‘Man, I reached for my phone that wasn’t even in my pocket.’”

I think my diagnosis looks pretty good. As I attempt a series of pretzel poses for which the class has not even remotely warmed up, I don’t feel the usual urge to do something more productive (which would include anything else, really). Though I don’t believe that reciting Sanskrit will somehow stop global warming, I’m not thinking about checking my email, either. Or about how crazy it is that I’m not using the Internet today (a thought trap my app-meditation teacher Puddicombe refers to in an email as “replacing being completely obsessed by using technology to being completely obsessed by *not* using technology”). I’m just going with it.

At least one study has suggested that even brief mindfulness training can create progress. Maybe my weeks of electronic peace are paying dividends in my weekend of disconnected peace.

The teacher’s iPod auto-shuffles from meditative music to a lecture about (you guessed it!) world peace. “All right, maybe we need to hear this,” she jokes, letting it play. Then a few minutes later, expressing her great satisfaction with the message, she shrieks, “oh my goodness, I have goosebumps!”

She laughs again. “Guess we’ll let God be the DJ,” she says.

“That’s not God,” I think to myself. “That’s Apple.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.