Making people laugh is not rocket science. It is (a kind of) science, though.

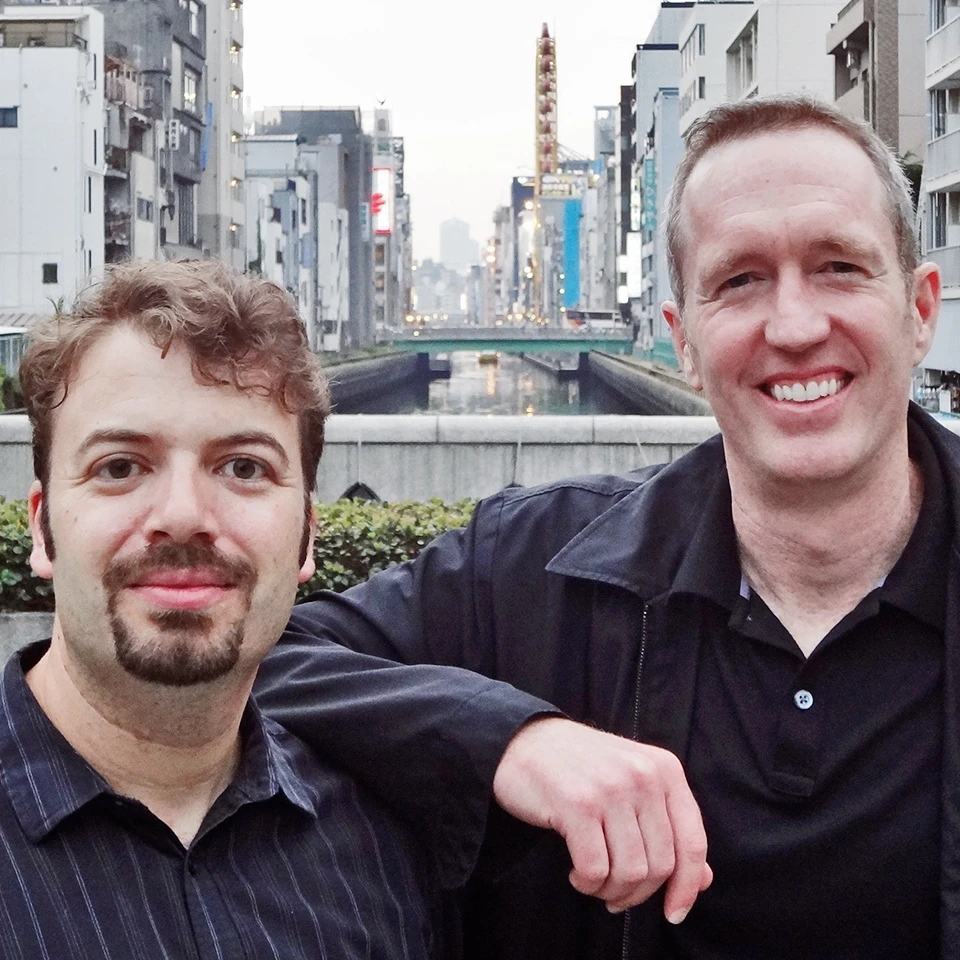

Anyone who’s ever wondered precisely why their joke did not land has a patron saint in professor Peter McGraw, who has plumbed the depths of human behavior to determine what is funny and what is not. Along with co-writer Joel Warner, McGraw has explored comedy all over the world, from the sets of Tokyo’s bizarre game shows to Palestine’s version of Saturday Night Live, and beyond. This exploration has resulted in a book called The Humor Code, and a reasonable scientific explanation for why people laugh at certain things and not others.

“Humor arises when something seems wrong, unsettling, or threatening (a kind of violation), but simultaneously seems okay, acceptable, or safe,” McGraw says. This idea makes up his Benign Violation theory, and it serves as the engine driving the book. “A dirty joke trades on moral or social violations, but it’s only going to get a laugh if the person listening is liberated enough to consider risqué subjects okay.” He adds, “Even tickling, which has long been a sticking point for other humor theories, fits perfectly. Tickling involves violating someone’s physical space in a benign way. You can’t tickle yourself because it isn’t a violation. Nor will you laugh if a creepy stranger tries to tickle you, since nothing about that is benign.”

For his part, Warner posits a much simpler explanation about what makes something funny: farts. (Not all theories require heavy academic research.) The co-author first became interested in humor as a topic in 2010, when he caught wind of McGraw’s academically-sanctioned Humor Research Lab (affectionately nicknamed HuRL). The professor had been at it for years, obsessed with uncovering why an anecdote he’d mentioned in a speech at Tulane fetched unlikely laughs from the crowd. Once Warner observed one of McGraw’s experiment in which participants watch Hot Tub Time Machine while sitting at various locations in a room, he saw a story in McGraw’s quest to find out, on a scientific level, what makes things laugh-worthy. The two soon joined forces.

McGraw developed his benign violation concept by modifying and expanding on an earlier linguist’s theory, one whose definitions didn’t seem to cover the right bases. The professor has been conducting rigorous scientific testing at HuRL and in his travels with Warner ever since, and thus far the concept has held water. Unlike other humor theories, such as superiority theory, incongruity theory, and relief theory, benign violation offers more explanations for why some things aren’t funny.

“A joke can fail in one of two ways,” he says. “It can be too benign, and therefore boring, or it can be too much of a violation, and therefore offensive.”

The only way for people who want to be funny, perhaps professionally, to know the difference is to approach their humor the way McGraw and Warner have: like scientists.

“It might not seem like it, but the best comedians hone their material scientifically, by experimenting bit by bit,” says Warner. “And the only way to learn is through hard, repetitive, empirical work. You get up there on that stage night after night, gauge which lines work and which don’t, and adjust accordingly.”

And if that doesn’t work, well, there’s always the farting option.

Below, read through McGraw and Warner’s explanations for whether a sampling of stand-up, movie, and sketch clips are funny.

#1) Dumb & Dumber, peppers scene

We don’t find this sort of gross slapstick particularly hilarious. (We, like all astute comedy aficionados, prefer to chuckle modestly at New Yorker cartoons while drinking cognac.) However, we will admit that broad, physical, and yes, stupid comedy like this has a pretty good shot at being funny all over the world.

Take the work of British psychology professor Richard Wiseman. In 2001, Wiseman set out to find the world’s funnies joke. Over twelve months, his “LaughLab” website clocked 40,000 joke submissions and nearly 2 million ratings from people in 40 different countries–the largest-ever scientific humor study. According to the results, this was the funniest joke:

“Two hunters are out in the woods when one of them collapses. He doesn’t seem to be breathing and his eyes are glazed. The other guy whips out his phone and calls emergency services. He gasps, ‘My friend is dead! What can I do?’ The operator says, ‘Calm down. I can help. First, let’s make sure he’s dead.’ There is a silence, then a gun shot. Back on the phone, the guy says, “Okay, now what?'”

We met Wiseman in London, and he had nothing good to say about this zinger. “I think the world’s funniest joke isn’t very funny,” he grumbled. “It’s terrible. I think we found the world’s cleanest, blandest, most internationally accepted joke. It’s the color beige in joke form.”

This makes sense. Universal comedy isn’t going to be the stuff that the most people find hilarious, it’s going to be the stuff that the least number of people find offensive. Any joke that makes fun of a particular people, religion, occupation, or viewpoint isn’t going to fly. It has to be something that’s acceptable to everybody–or in other words, something that’s a bit stupid. And Dumb and Dumber is as stupid as it gets.

#2) Tig Notaro’s Taylor Dayne story

According to Pete’s benign violation theory, people can employ one of two strategies to improve their shtick: they can make upsetting concepts more amusing by making them seem more benign (aka the Sarah Silverman Strategy, after the comedian who gets away with jokes on abortion and AIDS because the way she tells them is so darn cute), or they can point out what is hilariously wrong with our benign, everyday concepts (aka the Seinfeld Strategy: “What’s up with that airplane food?”). Tig Notaro is incredibly skilled in the Seinfeld Strategy, pointing out the absurdity in the stuff that most people take for granted.

Here, she even uses the strategy to point out the absurdity of her own routine: I’ve forgotten what to say next, and yet still you people are laughing! Why would I make up a story about a singer none of you have heard of, that doesn’t even have a good punch line! Plus, Tig Notaro is magical. She makes everything funny. Have you seen the bit where she does nothing but push a stool across a stage, and yet still the audience is loving it? In that case, art trumps science.

#3) Key & Peele’s East-West Bowl sketch

Wait, you want two geeky white guys to explain what makes a Key and Peele sketch involving convoluted African-American names funny? Fat chance. That, according to science, would be a pure violation. Please get us a grad student to figure it out for us.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.